- Home

- Part 1 Introduction, Quality

- Part 1. Introduction

- Part 1.2. Quality Management and Examination Quality Standards

- Part 1.3. Practice Change Procedure

- Part 2 General Filing Requirements

- Part 2. Landing Page

- Part 2.1. How a document is filed

- Part 2.2. Filing of Documents - requirements as to form

- Part 2.3. Non-compliance with filing requirements

- Part 2.4. Filing Process (excluding filing of applications for registration)

- Part 3 Filing Requirements for a Trade Mark Application

- Part 3. Relevant Legislation

- Part 3.1. Who may apply?

- Part 3.2. Form of the application

- Part 3.3. Information required in the application

- Part 3.4. When is an application taken to have been filed?

- Part 3.5. The minimum filing requirements

- Part 3.6. Consequences of non compliance with minimum filing requirements

- Part 3.7. Other filing requirements

- Part 3.8. Fees

- Part 3.9. Process procedures for non payment or underpayment of the appropriate fee

- Part 3.10. Process procedures for the filing of a trade mark application

- Part 4 Fees

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Fees - general

- 2. Circumstances in which fees are refunded or waived

- 3. Procedures for dealing with "fee" correspondence

- 4. Underpayments

- 5. Refunds and or waivers

- 6. No fee paid

- 7. Electronic transfers

- 8. Disputed credit card payments/Dishonoured cheques

- Part 5 Data Capture and Indexing

- Part 6 Expedited Examination

- Part 7 Withdrawal of Applications, Notices and Requests

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Withdrawal of an application, notice or request

- 2. Who can withdraw an application, notice or request?

- 3. Procedure for withdrawal of an application, notice or request

- 4. Procedure for withdrawal of an application to register a trade mark

- Part 8 Amalgamation (Linking) of Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Amalgamation of applications for Registration (Transitional)

- 2. Amalgamation (Linking) of Trade Marks under the Trade Marks Amendment Act 2006

- Part 9 Amendments and Changes to Name and Address

- Part 9. Landing Page

- Part 9. 1. Introduction

- Part 9. 2. Amendment of an application for a registration of a trade mark - general information

- Part 9. 3. Amendment before particulars of an application are published (Section 64)

- Part 9. 4. Amendment after particulars of an application have been published (Sections 63, 65 and 65A)

- Part 9. 5. Amendments to other documents

- Part 9. 6. Amendments after registration

- Part 9. 7. Changes of name, address and address for service

- Part 9. 8. Process for amendments under subsection 63(1)

- Part 10 Details of Formality Requirements

- Relevant Legislation

- Introduction

- 1. Formality requirements - Name

- 2. Formality requirements - Identity

- 3. Representation of the Trade Mark - General

- 4. Translation/transliteration of Non-English words and non-Roman characters

- 5. Specification of goods and/or services

- 6. Address for service

- 7. Signature

- 8. Complying with formality requirements

- Annex A1 - Abbreviations of types of companies recognised as bodies corporate

- Annex A2 - Identity of the applicant

- Part 11 Convention Applications

- Part 11. Landing Page

- Part 11.1. Applications in Australia (convention applications) where the applicant claims a right of priority

- Part 11.2. Making a claim for priority

- Part 11.3. Examination of applications claiming convention priority

- Part 11.4. Convention documents

- Part 11.5. Cases where multiple priority dates apply

- Part 11.6. Recording the claim

- Part 11.7. Effect on registration of a claim for priority based on an earlier application

- Part 12 Divisional Applications

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Divisional applications - general

- 2. Why file a divisional application?

- 3. Conditions for a valid divisional application filed on or after 27 March 2007

- 4. In whose name may a divisional application be filed?

- 5. Convention claims and divisional applications

- 6. Can a divisional application be based on a parent application which is itself a divisional application? What is the filing date in this situation?

- 7. Can the divisional details be deleted from a valid divisional application?

- 8. Divisional applications and late citations - additional fifteen months

- 9. Divisional Applications and the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012

- Annex A1 Divisional Checklist

- Part 13 Application to Register a Series of Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Series of Trade Marks - Act

- 2. Material Particulars

- 3. Provisions of Paragraphs 51(1)(a),(b) and (c)

- 4. Applying Requirements for Material Particulars and Provisions of Paragraphs 51(1)(a), (b) and (c)

- 5. Restrict to Accord

- 6. Examples of Valid Series Trade Marks

- 7. Examples of Invalid Series Trade Marks

- 8. Divisional Applications from Series

- 9. Linking of Series Applications

- 10. Colour Endorsements

- Part 14 Classification of Goods and Services

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. The purpose of classification

- 2. The classification system

- 3. Requirement for a clear specification and for correct classification

- 4. Classification procedures in examination

- 5. Principles of classification and finding the correct class for specific items

- 6. Wording of the specification

- 7. Interpretation of specifications

- 8. International Convention Documents

- Annex A1 - History of the classification system

- Annex A2 - Principles of classification

- Annex A3 - Registered words which are not acceptable in specifications of goods and services

- Annex A4 - Searching the NICE classification

- Annex A5 - Using the Trade Marks Classification Search

- Annex A6 - Cross search classes - pre-June 2000

- Annex A7 - Cross search classes - June 2000 to December 2001

- Annex A8 - Cross search classes from 1 January 2002

- Annex A9 - Cross search classes from November 2005

- Annex A10 - Cross search classes from March 2007

- Annex A11 - Cross search classes from January 2012

- Annex A12 - Cross search classes from January 2015

- Annex A13 - List of terms too broad for classification

- Part 15 General Provision for Extensions of Time

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. When the general provision applies

- 2. When the general provision does not apply

- 3. Circumstances in which the Registrar must extend time

- 4. Grounds on which the Registrar may grant an extension of time

- 5. Form of the application

- 6. Extensions of time of more than three months

- 7. Review of the Registrar's decision

- Part 16 Time Limits for Acceptance of an Application for Registration

- Part 16. Landing Page

- Part 16.1. What are the time limits for acceptance of an application to register a trade mark?

- Part 16.2. Response to an examination report received within four (or less) weeks of lapsing date

- Part 17 Deferment of Acceptance

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Deferment of Acceptance - introduction

- 2. Circumstances under which deferments will be granted

- 3. Period of deferment and termination

- 4. The deferment process where the applicant has requested deferment

- 5. The deferment process where the Registrar may grant deferment on his or her own initiative

- Annex A1 - Deferment of acceptance date - Grounds and time limits

- Part 18 Finalisation of Application for Registration

- Part 18. Landing Page

- Part 18.1. Introduction

- Part 18.2. Accepting an application for registration

- Part 18.3. Rejection of an application for registration

- Part 19A Use of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Use of a trade mark generally

- 2. Use 'as a trade mark'

- 3. Use 'in the course of trade'

- 4. Australian Use

- 5. Use 'in relation to goods or services'

- 6. Use by the trade mark owner, predecessor in title or an authorised user

- 7. Use of a trade mark with additions or alterations

- 8. Use of multiple trade marks

- Part 19B Rights Given by Registration of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. The trade mark as property

- 2. What rights are given by trade mark registration?

- 3. Rights of an authorised user of a registered trade mark

- 4. The right to take infringement action

- 5. Loss of exclusive rights

- Part 20 Definition of a Trade Mark and Presumption of Registrability

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Definition of a trade mark

- 2. Background to definition of a trade mark

- 3. Definition of sign

- 4. Presumption of registrability

- 5. Grounds for rejection and the presumption of registrability

- Part 21 Non-traditional Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Non-traditional signs

- 2. Representing non-traditional signs

- 3. Shape (three-dimensional) trade marks

- 4. Colour and coloured trade marks

- 5. "Sensory" trade marks - sounds and scents

- 6. Sound (auditory) trade marks

- 7. Scent trade marks

- 8. Composite trade marks - combinations of shapes, colours, words etc

- 9. Moving images, holograms and gestures

- 10. Other kinds of non-traditional signs

- Part 22 Section 41 - Capable of Distinguishing

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Registrability under section 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995

- 2. Presumption of registrability

- 3. Inherent adaptation to distinguish

- 4. Trade marks considered sufficiently inherently capable of distinguishing

- 5. Trade marks that have limited inherent capacity to distinguish but are not prima facie capable of distinguishing

- 6. Trade marks having no inherent adaptation to distinguish

- 7. Examination

- Registrability of Various Kinds of Signs

- 8. Letters

- 9. Words

- 10. Phonetic equivalents, misspellings and combinations of known words

- 11. Words in Languages other than English

- 12. Slogans, phrases and multiple words

- 13. Common formats for trade marks

- 14. New terminology and "fashionable" words

- 15. Geographical names

- 16. Surnames

- 17. Name of a person

- 18. Summary of examination practice in relation to names

- 19. Corporate names

- 20. Titles of well known books, novels, stories, plays, films, stage shows, songs and musical works

- 21. Titles of other books or media

- 22. Numerals

- 23. Combinations of letters and numerals

- 24. Trade marks for pharmaceutical or veterinary substances

- 25. Devices

- 26. Composite trade marks

- 27. Trade marks that include plant varietal name

- Annex A1 Section 41 prior to Raising the Bar

- Annex A2 Flowchart of "Capable of Distinguishing"

- Part 23 Overcoming Grounds for Rejection under Section 41 - including Evidence of Use

- Part 23. Landing Page

- Part 23.1. Introduction

- Part 23.2 Submissions in rebuttal, amendments and informal information

- Part 23.3 Evidence of use - general requirements

- Part 23.4 Examining evidence - general

- Part 23.5 Specific evidence requirements for trade marks with no inherent adaptation to distinguish

- Part 23.6 Endorsements for applications overcoming section 41 grounds for rejection

- Part 23. Annex A1 - Information for applicants on the preparation and presentation of a declaration including model layout

- Part 23. Annex A2 - Model layout for statutory declaration/affidavit

- Part 23. Annex A3 - Model layout for supporting statutory declaration

- Annex A4 - How to supply evidence of use of a Trade Mark under subsection 41(5) - for trade marks with a filing date prior to 15 April 2013

- Annex A5 - How to supply evidence for use of a Trade Mark under subsection 41(6) - for trade marks with a filing date prior to 15 April 2013

- Annex A6 - How to supply evidence of use of a trade mark under subsection 41(4) - for trade marks with a filing date on or after 15 April 2013

- Annex A7 - How to supply evidence of use of a trade mark under subsection 41(3) - for trade marks with a filing date on or after 15 April 2013

- Part 24 Disclaimers

- Part 24. Landing Page

- Part 24.1. What is a disclaimer?

- Part 24.2. Request for a voluntary disclaimer

- Part 24.3. Effect of a disclaimer on registration

- Part 24.4. Effect of a disclaimer on examination

- Part 24.5. Amendment of disclaimers

- Part 24.6. Revocation of disclaimers

- Part 26 Section 44 and Regulation 4.15A - Conflict with Other Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction to section 44 and regulation 4.15A

- 2. Presumption of registrability and the application of section 44

- 3. Cross Class Search List

- 4. Similarity of goods and services

- 5. Similarity of trade marks

- 6. Factors to consider when comparing trade marks

- 7. Trade marks with the same priority/filing date

- 8. Assignment of applications and registrations

- 9. Grounds for rejection when the citation is in its renewal period

- Annex A1 - Citing multiple names

- Part 27 Overcoming Grounds for Rejection under Section 44

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 3. Amending the goods and/or services of the applicant's specification

- 4. Negotiation with owner/s of conflicting trade mark/s

- 5. Filing evidence of honest concurrent use, prior use or other circumstances

- 6. Removal of the conflicting trade mark

- 7. Dividing the application

- Annex A1 - An example of a letter of consent

- 2. Legal submissions

- Part 28 Honest Concurrent Use, Prior Use or Other Circumstances

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Honest concurrent use - paragraph 44(3)(a)

- 3. Examining evidence of honest concurrent use - the five criteria

- 4. Other circumstances - paragraph 44(3)(b)

- 5. Conditions and limitations to applications proceeding under subsection 44(3)

- 6. Prior use - subsection 44(4)

- 7. Examining evidence of prior use

- 8. Endorsements where the provisions of subsection 44(3) or 44(4) and/or reg 4.15A are applied

- Annex A1 - Information sheet for trade mark applicants - Evidence of honest and concurrent, prior use or other circumstances

- Part 29 Section 43 - Trade Marks likely to Deceive or Cause Confusion

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Trade marks likely to deceive or cause confusion

- 2. Connotation

- 3. Deception and confusion as a result of a connotation within a trade mark

- 4. Descriptions of goods/services

- 5. International Non-Proprietary Names and INN Stems

- 6. Names of Persons

- 7. Phonewords and Phone Numbers

- 8. Internet Domain Names

- 9. Geographical References

- 10. Claims to Indigenous Origin

- Annex A1 - Table of INN stems

- Part 30 Signs that are Scandalous and Use Contrary to Law

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Scandalous signs

- 3. Use contrary to law

- Annex A1 - Examples of Legislation which may trigger the provisions of section 42(b)

- Annex A2 - Official notice re copyright in the Aboriginal Flag

- Annex A3 - Defence force prohibited terms and emblems

- Annex A4 - Major Sporting Events protected words

- Annex A5 - Examples regarding Geneva Conventions Act 1957 s 15(1)

- Part 31 Prescribed and Prohibited Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Prohibited signs - subsection 39(1)

- 2. Prescribed signs - subsection 39(2)

- 3. When does a ground for rejection exist under subsection 39(2)?

- 4. Practice regarding the signs prescribed under subsection 39(2) appearing in subreg 4.15

- 5. Other information relevant to examining trade marks that contain a prohibited and prescribed sign

- Part 32A Examination of Trade Marks for Plants (in Class 31)

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Examination of Plant Trade Marks

- 2.1 Section 42: Contrary to Law

- 2.2 Section 39: Prescribed Signs

- 2.3 Section 41: Capacity to Distinguish

- 2.4 Section 43: Deception and Confusion

- 2.5 Section 44: Comparison of Trade Marks

- 2.6 Non-Roman characters (NRC) and transliterations in class 31 plant examination

- Annex 1 - Applicable Section of the PBR Act

- Annex 2 - Applicable Sections of the UPOV Convention

- Annex 3 - Applicable Sections of the ICNCP

- Annex 4 - An Example of a PBR Letter of Consent

- Annex 5 - Case Law Summaries

- Annex 6 - How to Supply Evidence of Use of a Trade Mark for Plants and/or Plant Material

- Part 32B Examination of Trade Marks for Wines (in Class 33)

- Part 32B: Landing Page

- Part 32B.1. Introduction

- Part 32B.2. Examination of Wine Trade Marks

- Part 32B.2.1 Section 42: Contrary to Law

- Part 32B.2.2 Section 43: Deception and Confusion

- Part 32B.2.3 Section 41: Capacity to Distinguish

- Part 32B.2.4 Section 44: Comparison of Trade Marks

- Part 32B.3. Protected Terms in Specifications of Goods

- Part 33 Collective Trade Marks

- Part 33. Landing Page

- Part 33.1. What is a collective trademark?

- Part 33.2. Application of Act

- Part 33.3. Application for registration

- Part 33.4. Limitation on rights given by registered collective trade marks

- Part 33.5. Assignment or transmission of collective trade marks

- Part 33.6. Infringement of collective trade marks

- Part 34 Defensive Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Australian trade marks law and defensive trade marks

- 2. Requirements for the filing of a defensive trade mark

- 3. Section of the Act NOT applying to defensive trade marks

- 4. Registrability of defensive trade marks

- 5. Grounds for rejection under Division 2 of Part 4 of the Act

- 6. Grounds for rejecting a defensive application under section 187

- 7. Evidence required for defensive applications

- 8. Rights given by defensive registration

- 9. Grounds for opposing a defensive registration

- 10. Cancellation of defensive trade marks

- Part 35 Certification Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is a certification trade mark?

- 2. Certification trade marks and geographical indications (GIs)

- 3. Sections of the Act NOT applying to certification trade marks

- 4. The registrability of certification trade marks

- 5. Rights given by, and rules governing the use of, certification trade marks

- 6. Assessment by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)

- 7. Opposition to the registration of a certification trade mark

- 8. Variation of rules

- 9. Assignment of registered certification trade marks

- 10. Assignment of unregistered certification trade marks

- 11. Transmission of certification trade marks

- 12. Rectification of the Register and variation of rules by order of the court

- Annex A1 - Certification Trade Marks flow chart

- Part 38 Revocation of Acceptance

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is revocation of acceptance?

- 2. Reasons for revocation

- 3. Revocation process

- Part 39 Registration of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Overview of registration

- 2. Particulars of registration

- 3. Format of Certificate of registration

- 4. Timing

- 5. Date and term of registration

- 6. Registration fees

- 7. Registration process

- 8. Notification of Protection process for International Registrations Designating Australia

- Annex A1 - Certificate of Registration

- Part 40 Renewal of Registration

- Part 40. Landing Page

- Part 40.1. What is renewal?

- Part 40.2. Timing for renewal

- Part 40.3. Late renewal

- Part 40.4. Failure to renew

- Part 41 Cancellation of Registration

- Part 41. Landing Page

- Part 41.1. What is the effect of cancelling a registration?

- Part 41.2. Why is a registration cancelled?

- Part 41.3. Cancellation process

- Part 42 Rectification of the Register

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is rectification?

- 2. What part does the Registrar play in rectification actions brought by a person aggrieved?

- 3. Rectification procedures

- Annex A1 - Flow chart of rectification procedure

- Part 43 Assignment and Transmission

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is assignment and transmission?

- 2. Timing for assignment

- 3. Application to record assignment etc

- 4. Process for assigning all goods and/or services (full assignment)

- 5. Process for assigning only some goods and/or services (partial assignment)

- 6. Process for assignment of certification trade marks

- 7. Transmission of certification trade marks

- Part 44 Claim of Interest or Rights in a Trade Mark

- Part 44. Landing Page

- Part 44.1. Background

- Part 44.2. Effect of recording the claim

- Part 44.3. When can the interest be recorded?

- Part 44.4. Recording the claim

- Part 44.5. Amending the record of a claim

- Part 44.6. Cancelling the record of a claim

- Part 45 Copies of Documents

- Part 45. Landing Page

- Part 45.1. Documents copied by the Office

- Part 45.2. Types of document copies and delivery dispatch

- Annex A1 - Flow chart of production of copies/certified copies

- Part 46 Grounds for Opposition to Registration or Protection

- Relevant Legislation

- References used in this part

- 1. What is opposition to registration or protection?

- 2. The Registrar’s role in an opposition

- 3. When registration or protection can be opposed

- 4. Grounds for opposition to registration of national trade marks

- 5. Grounds for opposition to protection of international trade marks

- Part 47 Procedures for Opposing Registration or Protection

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Filing a notice of opposition

- 2. Request to amend a notice of intention to oppose or a statement of grounds and particulars

- 3. Filing a notice of intention to defend

- 4. Opposition may proceed in the name of another person

- 5. Making Convention documents available to opponent

- Part 48 Removal of a Trade Mark from the Register for Non-use

- Relevant legislation

- References used in this part

- 1. What if a trade mark is not used?

- 2. Application for removal/cessation of protection for non-use

- 3. Opposition to a non-use application

- 4. Application for extension of time to oppose the non-use application where the trade mark is already removed

- 5. Grounds on which a non-use application may be made

- 6. Burden on opponent to establish use of a trade mark

- 7. Authorised use by another person

- 8. Use by an assignee

- 9. Localised use of trade mark

- 10. Circumstances that were an obstacle to the use of a trade mark

- 11. Where there is no evidence in support of the opposition

- 12. Registrar's discretion in deciding an opposed non-use application

- 13. Registrar to comply with order of court

- 14. Right of appeal

- 15. Certificate - Use of a trade mark

- Part 49 Non-use Procedures

- Relevant legislation

- 1. Application for removal or cessation of protection of a trade mark for non-use

- 2. Opposition to non-use application

- 3. Amendment to notice of intention to oppose or statement of grounds and particulars

- 4. Notice of intention to defend

- 5. Opposition may proceed in the name of another person

- 6. Opposition proceedings

- Part 51 General Opposition Proceedings

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Evidence

- 2. Extension of the period for filing evidence

- 3. Cooling-Off Period

- 4. Suspensions

- 5. Hearing of the opposition

- 6. Dismissal or discontinuance of proceedings

- 7. Award of costs

- 8. Rights of appeal

- 9. Period in which a trade mark can be registered/protected

- 10. Guidelines for Revocation of Acceptance of Opposed trade marks

- 11. Unilateral Communications with Hearing Officers

- Part 52 Hearings, Decisions, Reasons and Appeals

- Relevant Legislation

- References used in this Part

- 1. What is a decision?

- 2. What is a hearing?

- 3. Is a hearing always necessary?

- 4. Role and powers of the Registrar in hearings

- 5. Rights of appeal from decisions of the Registrar

- 6. Appeals from decisions of the Federal Court etc.

- 7. Implementation of decisions

- 8. Service of documents on the Registrar

- Part 54 Subpoenas, Summonses and Production of Documents

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Subpoenas

- 2. Summonsing a witness

- 3. Production of documents

- Annex A1 - Consequences of mishandling a subpoena

- Annex A2 - Format of a summons to witness

- Annex A3 - Format of notice requiring production

- Part 55 Costs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Legislative Basis

- 2. Award of costs

- 3. Applications for an award of costs

- 4. Determination of the amount of costs

- 5. Full costs where certificate of use of a trade mark provided to removal applicant

- 6. Costs recovery

- 7. Security for costs

- Annex A1 - Taxing of costs in "multiple" oppositions relying on same evidence

- Part 60 The Madrid Protocol

- Relevant Legislation

- Glossary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. International Applications

- 2.1 General Description

- 2.2 International Application Form

- 2.3 Data Entry

- 2.4 Certifying Process

- 2.5 Fees for International Applications

- 2.6 Renewal

- 3. The Basic Application or Basic Registration (Basic Trade Mark)

- 4. International Registrations that have Designated Australia

- 4.1 General Description

- 4.2 Record of International Registrations

- 4.3 Filing/Data Capture/Allocation of Australian Trade Mark Number

- 4.4 Indexing

- 4.5 Expedite

- 4.6 Classification of Goods and Services

- 4.7 Examination of an IRDA

- 4.8 Reporting on an IRDA

- 4.9 Provisional Refusal

- 4.10 Amendments

- 4.11 Deferment of Acceptance

- 4.12 Extension of Time

- 4.13 Final Decision on Provisional Refusal Based on Examination

- 4.14 Acceptance

- 4.15 Revocation of Acceptance

- 4.16 Extension of Time to File Notice of Opposition to Protection

- 4.17 Opposition to Protection

- 4.18 Protection

- 4.19 Cessation or Limitation of Protection

- 4.20 Cessation of Protection because of Non-Use

- 4.21 Opposition to Cessation of Protection because of Non-Use

- 4.22 Renewal

- 4.23 Claim to Interest in, or Right in Respect of a Trade Mark

- 4.24 Change in Ownership of an International Registration

- 4.25 Transformation

- 4.26 Replacement

- 4.27 Customs

- Part 61 Availability of Documents

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Availability of Documents

- 2. Accessing Documents

- 3. Documents to be made Available for Public Inspection (API)

- 4. Information that the Registrar of Trade Marks will Not Accept in Confidence

- 5. Confidential Information in Correspondence

- 6. Policy in relation to TM Headstart

- Part 62 Revocation of Registration

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is revocation of registration?

- 2. Prerequisites to revocation of registration

- 3. Factors to be taken into account before deciding whether revocation of registration is reasonable

- 4. Circumstances under which registration may be revoked

- 5. Mandatory revocation

- 6. Right of appeal: revocation of registration

- 7. Extension of time

- 8. Amendment or cessation of protection by Registrar of Protected International Trade Marks (PITMs)

- 9. Registrar must notify Customs if protection of a PITM is revoked

- 10. Right of appeal: cessation of protection

19A.2. Use 'as a trade mark'

Not all use of a particular sign will constitute use ‘as a trade mark’. In Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721 at [19], the Full Bench of the Federal Court held :

Use 'as a trade mark' is use of the mark as a 'badge of origin' in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods ... That is the concept embodied in the definition of 'trade mark' in s 17 – a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else.

This statement was expressly approved by a majority of the High Court in E. & J. Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Limited [2010] HCA 15 at [43].

In Self Care at [24], the High Court said:

Whether a sign has been "use[d] as a trade mark" is assessed objectively without reference to the subjective trading intentions of the user. As the meaning of a sign, such as a word, varies with the context in which the sign is used, the objective purpose and nature of use are assessed by reference to context. That context includes the relevant trade, the way in which the words have been displayed, and how the words would present themselves to persons who read them and form a view about what they connote.

The use of a trade mark to indicate a connection in the course of trade has been referred to as the ‘branding function’ of the trade mark (see Anheuser-Busch, Inc v Budejovický Budvar, Národní Podnik & Ors [2002] FCA 390 and Alcon Inc v Bausch & Lomb (Australia) Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 1299). In Nature's Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117 at [19], the Full Court held:

The appropriate question to ask is whether the impugned words would appear to consumers as possessing the character of the brand: Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422.

Use that is solely descriptive or laudatory is unlikely to be use of a sign as a ‘badge of origin’. Such use is therefore not use of a sign ‘as a trade mark’. However, the High Court in Self Care at [25] cautioned:

The existence of a descriptive element or purpose does not necessarily preclude the sign being used as a trade mark. Where there are several purposes for the use of the sign, if one purpose is to distinguish the goods provided in the course of trade that will be sufficient to establish use as a trade mark. Where there are several words or signs used in combination, the existence of a clear dominant "brand" is relevant to the assessment of what would be taken to be the effect of the balance of the label, but does not mean another part of the label cannot also act to distinguish the goods.

It will generally be more difficult to establish that use of a descriptive word is use of a sign ‘as a trade mark’. In Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH [2001] FCA 1874 at [23], Hill J held:

Where the word has or a combination of words have a clear meaning in ordinary use, the question will be much more difficult as the word or combination of words may either have taken on a secondary meaning indicating the origin of the goods or may simply convey an ordinary meaning (ie some message other than the trade origin of the goods): see Top Heavy Pty Ltd v Killin (1996) 34 IPR 282 at 286.

However, his Honour went on to say at [23]:

It is well established that there is not a true dichotomy between words capable of being used as a badge of trade origin and words that are descriptive: see Johnson & Johnson at 347 per Gummow J and at 339 per Lockhart J.

In Woolworths Limited v BP Plc (No. 2) [2006] FCAFC 132 at [77] ('BP'), the Full Court commented:

How the mark has been used may not involve a single or clear idea or message. The mark may be used for a number of purposes, or to a number of ends, but there will be use as a trade mark if one aspect of the use is to distinguish the goods or services provided by a person in the course of trade from the goods or services provided by any other persons, that is to say it must distinguish them in the sense of indicating origin…

In Nature's Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117 at [19], in the context of infringement proceedings relating to a sign used on goods and in the presence of other distinctive material, the Full Court held:

Consideration of the totality of the packaging, including the way in which the words are displayed in relation to the goods and the existence of a label of a clear and dominant brand, are relevant in determining the purpose and nature (or ‘context’) of the impugned words: Johnson & Johnson at 347; Anheuser-Busch, Inc v Budějovický Budvar, Národní Podnik [2002] FCA 390

Set out below (2.1-2.4) is a discussion of the use of signs in particular circumstances and whether this constitutes use ‘as a trade mark’. Paragraph 2.5 contains some illustrative examples that assist in understanding and applying the abstract concepts discussed above. A summary of the relevant considerations is set out in 2.6

2.1 Aural use

An aural representation of a trade mark that consists of a letter, word, name or numeral, or any combination thereof, is considered use of the trade mark for the purposes of the Act (s 7(2)).

Corroborated recollection of a conversation in which a trade mark has been referred to in relation to a commercial product available for purchase has been held by the Federal Court to constitute sufficient evidence of use as a trade mark - Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 464 at [571] (‘Rakman’). However, in the same case, Yates J confirmed that caution must be exercised in accepting such evidence, and rejected other evidence of conversations on the basis that they did not occur in the course of trade (at [580]) or that the evidence did not establish that reference to the trade mark occurred in the course of particular meetings (at [595] to [597]).

Aural use of a trade mark may in some cases be inferred. For instance, use of a composite mark containing word and device elements is likely to also lead to aural use of the word alone in circumstances where the trade mark is referred to during verbal dealings for the goods or services (for example, where goods are normally ordered over the phone). It is important, however, to consider the limitations of this use as well. Aural use to refer a composite mark, is not use of the composite mark itself. It is use of the letter, word, name or numeral, or any combination thereof which appears within a composite mark. It might be use of a substantially identical mark but that is a question of how much graphic or other material is included in the composite mark beyond the letter, word, name or numeral, or any combination thereof.

2.2 Use as a domain name, key word, metatag, social media account name or handle

It is common for many traders to provide their goods or services via a website that is identified by a domain name. Use of a domain name may in some circumstances constitute use of a trade mark. In Sports Warehouse, Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664, Kenny J held at [153]:

It is not suggested that mere registration of a domain name can amount to use of the mark. More must be shown. Plainly enough, not all domain names will be used as a sign to distinguish the goods or services of one trader in the course of trade from the goods or services of another trader. Sports Warehouse is correct in its submission that that whether or not a domain name is used as a trade mark will depend on the context in which the domain name is used. In this case, the domain name is more than an address for a website, the domain name is also a sign for the Applicant’s online retailing service available at the website. In the context of online services, the public is likely to understand a domain name consisting of the trade mark (or something very like it) as a sign for the online services identified by the trade mark as available at the webpage to which it carries the internet user.

Goods or services available via websites are generally located via internet search engines. Internet search engine providers often sell words or phrases corresponding to registered trade marks as ‘key words’ or ‘metatags’. A purchaser of a key word or metatag will generally have their website prioritised in search results for that key word or metatag. Metatags contain computer coding statement of the content of a particular website and are used by search engines to index and find a page. The practice by search engines to optimise or rank the priority of a website appearing in its search result by metatag is sometimes referred to as ‘Ad Word’ or key word advertising.

In Advantage Veda Advantage Ltd v Malouf Group Enterprises Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 255 and Complete Technology Integrations Pty Ltd v Green Energy Management Solutions Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1319, the Federal Court held that the metatag use was not use as a trade mark because it was not visible to the ordinary internet user. However, in Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 56, the Full Court affirmed a decision by the primary judge that use of HARBOUR LIGHTS in source code of its website was use as a trade mark for the purpose of determining an infringement claim. This was despite the fact that there was no evidence that anyone saw the metadata.

Evidence of use of a trade mark as metadata should be treated with caution for the purposes of assessing registrability under s 41 and s 44. In many cases, even if the use relied on is use ‘as a trade mark’ the weight that it should be given may be significantly diminished by the context of use. Further, metadata use is more likely to be relevant to infringement cases. It is unlikely that an applicant would rely solely on evidence of use as a metatag to support registration.

However, use in sponsored link advertisements (being visible to consumers) may constitute more compelling evidence of trade mark use.

The use of sign as an account name or handle on social media can also constitute ‘use as a trade mark’. In Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808, Burley J held at [324] that the use of the words LA FAMIGLIA RANA as the account name and @lafamigliarana as the handle on Facebook both constituted trade mark use. His honour said at [325]:

In my view each of the account names and the @lafamigliarana handles amount to trade mark uses. A consumer would not see them as merely being descriptive. They indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods: Johnson & Johnson (Lockhart J at 341, Burchett J at 342, Gummow J at 251); Shell Co (per Kitto J at 424-425, Dixon CJ, Taylor J and Owen J separately agreeing). They are used to identify the Rana Facebook page or Rana Instagram page, each of which provides a means by which goods sold by Rana are displayed and presented: see, by analogy in relation to a domain name Flexopack at [64] and Sports Warehouse at [154].

Using similar analysis, the Full Federal Court in Henley Constructions Pty Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 62 allowed Henley Properties’ cross-appeal and held that the phoneword 1300HENLEY was used as a trade mark. At [297], the Full Court said:

While, undoubtedly, Henley Constructions used the sign 1300HENLEY as a telephone number, it did so for promotional purposes—namely, to promote the name HENLEY as the source of the building and construction services that Henley Constructions was offering in trade. In this way, Henley Constructions was using 1300HENLEY as a sign to distinguish its services from the building and construction services provided by other traders.

2.3 Business names

A business name and a trade mark are related but different things. A business name is the name under which a business operates and if it is different from the name of person or company who carries on the business, it must be registered as a business name with ASIC. The allocation of a business name (or a company) by ASIC does not give the holder any rights to use that business or company name. Trade mark rights in a business or company name arise in two ways: by registration as a trade mark under the Trade Marks Act 1995 or by developing common law rights (reputation) through use of the business or company name. The purpose of the business name registration systems is to make readily available on the public records the operators of a business. It is administrative, not proprietary, in character. Registration of a business name in itself creates no intellectual property rights and is not prima facie evidence that a sign has been used ‘as a trade mark’.

In Shahin Enterprises Pty Ltd v Exxonmobil Oil Corporation [2005] FCA 1278 at [73], Lander J held:

There is a clear distinction, in my opinion, between conducting a business under a particular name and using a mark in respect of goods or services. The intention which the applicant needed to establish was an intention to use a mark to distinguish goods or services in the course of the applicant’s trade from goods or services provided by any other person. Because it has established that it intended to use the name to brand its businesses, that does not mean, however, it has established that it has used a mark or a sign to distinguish goods or services in the course of trade.

Whether a person has used a sign that constitutes their business name as ‘a trade mark’ will depend on whether they have used it as a badge of origin taking into account the considerations outlined above.

In many cases, particularly in relation to provision of services, the trade mark and business name will be one and the same, in that the same word or phrase will serve the dual purpose of being the name under which the business is carried on, and the name which distinguishes the services of that business.

2.4 Shape and colour trade marks

The normal rules apply when determining whether a shape or a colour has been used ‘as a trade mark’. However, the relationship of a shape or a colour to the relevant goods or services will influence how the general principles are applied.

In Global Brand Marketing Inc v YD Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 605 at 61, Sundberg J set out the criteria for determining whether use of a shape is use ‘as a trade mark’.

The principles relevant to use of shape as a trade mark are now set out.

a. A special shape which is the whole or part of goods may serve as a badge of origin. However the shape must have a feature that is ‘extra’ and distinct from the inherent form of the particular goods: Mayne at [67], Remington at [16] and Kenman Kandy at [137]

b. Non-descriptive features of a shape point towards a finding that such features are used for a trade mark purpose. Where features are striking, trade mark use will more readily be found. For example, features that make goods more arresting of appearance and more attractive may distinguish the goods from those of others: All-Fect at [25].

c. Descriptive features, like descriptive words, make it more difficult to establish that those features distinguish the product. For example, the word COLA or an ordinary straight walled bottle are descriptive features that would have limited trade mark significance: All-Fect at [25] and Mayne at [61]-[62].

d. Where the trade mark comprises a shape which involves a substantial functional element in the goods, references to the shape are almost certainly to the nature of the goods themselves rather than use of the shape as a trade mark: Mayne at [63]. For example, evidence that a shape was previously patented will weigh against a finding that the shape serves as a badge of origin: Remington at [12] and Mayne at [69].

e. If a shape or a feature of a shape is either concocted compared to the inherent form of the shaped goods or incidental to the subject matter of a patent, it is unlikely to be a shape having any functional element. This may point towards the shape being used as a trade mark: Kenman Kandy at [162] and Mayne at [69].

f. Whether a person has used a shape or a feature of a shape as a trade mark is a matter for the court, and cannot be governed by the absence of evidence on the point: All-Fect at [35].

g. Context "is all important" and will typically characterise the mark’s use as either trade mark use or not: Remington at [19] and Mayne at [60]-[62].

As is apparent from the foregoing propositions, a shape mark case may require consideration of different types of features in determining whether the mark is used as a trade mark for the purposes of the Act. At one end of the spectrum are shapes or features thereof that are purely functional. The features may have derived substantially from a patented product, such as the S-shaped fence dropper, or go to the usefulness of the product: Remington at [3] and [12]. Cases such as Mayne and Remington show that such features point away from trade mark use.

At the other end of the spectrum are those features of a mark that are non-descriptive and non-functional. They ordinarily make the shape more arresting of appearance and more attractive, thus providing a means of distinguishing the goods from those of others. All-Fect and Remington show that non-functional features add something extra to the inherent form of the shape. A concocted feature will typically be considered non-functional: Kenman Kandy.

Finally, there will be cases, such as the present, that fall between the ends of the spectrum. These cases are not black and white. They involve consideration of whether one set of features supersedes, submerges or overwhelms the other.

Similarly, considerations of functionality will be relevant in determining whether a colour has been used ‘as a trade mark’. In Philmac Pty Limited v The Registrar of Trade Marks [2002] FCA 1551 at 53, Mansfield J held:

… a trader might legitimately choose a colour for its practical utility. That is, the colour may be a feature of a product that serves to improve the functionality or durability of the product. The function of visibility is, for example, served by the colour yellow; heat absorption by the colour black; light reflection by the colour white; military camouflage by a combination of khaki, brown and green.

…

The shape mark cases properly indicate a reluctance to permit, by virtue of a trade mark registration, a permanent monopoly of matters of engineering design: Kenman per French J at [45]; Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products Australia Ltd [1999] FCA 816; (1999) 91 FCR 167; Philips Electronics NV v Remington Consumer Products (1997) 40 IPR 279 per Jacob J; British Sugar Plc v James Robertson & Sons Ltd [1996] RPC 281. In my view there is no reason why the functionality principles applied to the registration of shape marks should not also apply to the consideration of the application of colour marks.

It is important to bear in mind that even if an applicant can establish that a particular use of their shape or colour is use ‘as a trade mark’, that use may not be sufficient to demonstrate the mark is or will become capable of distinguishing for the purposes of s 41 (see Parts 21, 22 and 23).

2.5 Illustrative examples

It is not possible to list exhaustively all situations in which use ‘as a trade mark’ will or will not occur. However, the cases provide some illustrative examples.

Examples where use as a trade mark found

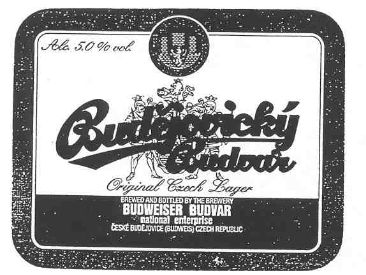

The High Court in Self Care v Allegan expressly approved at [25] Allsop J’s decision in Anheuser-Busch, Inc v Budejovicky Budvar, Narodni Podnik [2002] FCA 390 at [191] that Budejovicky Budvar used “Budweiser Budvar” as a trade mark on its labels and packaging notwithstanding the presence of a clear, dominant brand: Budejovicky Budvar. One of the labels in question was:

At [190]-[191] Allsop J explained:

[190] Here, dealing with Exhibit GRB 11 and Exhibit TH 10, the matters to which I have referred above, taken in conjunction with the fact that the words ‘Budweiser Budvar’, and the word ‘Budweiser’, are used in a collocation of words giving information about the trade connection and from the impression which I think someone who reads it will take, lead me to the conclusion that ‘Budweiser’ and ‘Budweiser Budvar’ is and are being used as trade marks on the orange strip.

[191] It is not to the point, with respect, to say that because another part of the label (the white section with ‘Budějovický Budvar’) is the obvious and important ‘brand’, that another part of the label cannot act to distinguish the goods. The ‘branding function’, if that expression is merely used as a synonym for the contents of ss 7 and 17 of the TM Act, can be carried out in different places on packaging, with different degrees of strength and subtlety. Of course, the existence on a label of a clear dominant ‘brand’ is of relevance to the assessment of what would be taken to be the effect of the balance of the label.

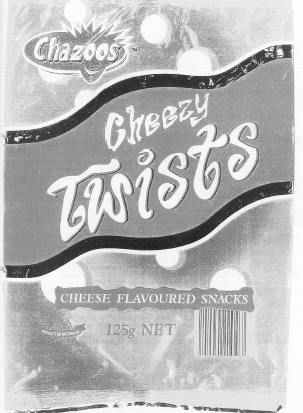

In Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH [2001] FCA 1874, the Full Court held that Aldi had used “Cheezy Twists” as a trade mark notwithstanding the descriptive nature of the phrase and the presence of a “house” brand “Chazoos”:

After discussing the principles at [26], Hill J said:

… While the words “Cheezy Twists” are capable of describing the contents of the package, my view is that they do much more than that. Such description is found on the packet in any event in the words “cheese flavoured snacks”, which on no view of the matter were used as a trade mark. While it is no doubt true to say that the word “Chazoos”, with or without logo, is used as a trade mark, the present is a case where two trade marks are used, one a generic word used over a product range and the other used as a badge of origin in respect of a particular product.

And at [80], Lindgren J said:

The distinctive form of the words “CHEEZY TWISTS”, their prominent position within the waving banner across the front of the packets, and the use of the obviously descriptive expression “cheese flavoured snacks” just below the banner, and, far less significantly, the misspelling of “CHEEZY”, all of which were referred to by his Honour, lead me to conclude that he did not err in finding that in the use it made of them on the packets, Aldi used the words “CHEEZY TWISTS” as a trade mark.

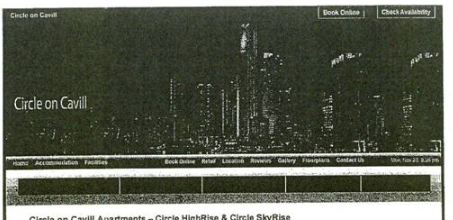

In Mantra Group Pty Ltd v Tailly Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 291, the court considered whether use of the words CIRCLE ON CAVILL by the respondent infringed various trade marks consisting of or containing these words. ‘Circle on Cavill’ was the name of an apartment complex on the Gold Coast in which accommodation could be rented.

Reeves J considered the context of the respondent’s use, particularly given the term ‘Circle on Cavill’ was also used in a descriptive capacity on the respondent’s website. He said at [57]:

However, when one looks at the uses Tailly has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” on its websites as a whole and in context, I consider this descriptive use of those words pales into insignificance by comparison to the other use Tailly has made of those words. Moreover, I consider the other use Tailly has made of those words clearly constitutes trade mark use. As to the descriptive use of those words, when one looks at each website, it is clear that the descriptive use appears in small font in the form of prose in the body of the website. On the other hand, the other use Tailly has made of the words “Circle on Cavill” appears at the head of the first page of each website in a banner-style heading in large font combined with a depictive background. Thus, when one compares the size, positioning and format of the descriptive use of the words “Circle on Cavill”, with the size, positioning and format of the banner heading use of those words, I consider that a member of the public, taking an objective view of the matter, would conclude that the primary, or most significant use of those words is as a badge or emblem to indicate that Tailly is the origin of the accommodation letting services at Circle on Cavill.

In BP, the Full Court held that the use of green and yellow (or gold) by BP as its corporate colours was to distinguish its goods and services from other oil companies (although the court ultimately held that such use did not align with the mark applied for – namely, the colour green by itself). The Full Court took into account the longstanding use of colour by oil companies as part of the getup of their service stations and the aural reference to the colours in advertisements by BP.

In RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10 at [93], the following trade mark (‘the 914 mark’) was the subject of discussion:

Use of this trade mark was contemplated in the context of evidence as shown below:

The Full Court found that some of the evidence demonstrated use of the shape as a trade mark. For example, in relation to the example shown on the right:

It is apparent that six capsules of the Quantum Product visible to the consumer through the clear window at the front of the packaging and arranged in a tessellate pattern show the red powerball centre and blue gel wave on top. They serve to provide a visual prompt to the consumer. In our respectful view, the primary judge failed to take into account that a display of the product could serve a dual function: not only to serve the descriptive function of showing the product for sale, but also serving to reinforce to the consumer that the product is the very one that comes from the supplier of FINISH products. Having found that the Quantum Product is substantially identical to the 914 mark, and after noting earlier that there is no functional basis for the placement of the components or colouring of the features of the 914 mark, they serving a purely aesthetic purpose (at [21]), in our view the primary judge ought also, having regard to the context of use in the Quantum Tablets Packaging, to have concluded that the display of the tablets reflected trade mark use. …As the High Court noted in Selfcare at [25], the existence of a descriptive element or purpose does not necessarily preclude the sign being used as a trade mark. In our view, in objective terms it may accurately be said that the display of the Quantum Product in the window serves, at least as one purpose, to distinguish the goods in the course of trade in reference to their origin.

It should be noted that not every use of a shape will constitute use as a trade mark simply because the shape is visible to the public on packaging or in other ways related to the sale or promotion of the product. The nature of the shape and context of its use of a particular shape will be the primary determinative factors as to whether it is being used as a trade mark in each case.

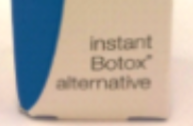

Factors taken into account include (i) the use of two clear ‘badges of origin’ FREEZEFRAME (umbrella brand) and INHIBOX (the name of the product), (ii) the small font in which ‘instant Botox(R) alternative’ was used, (iii) the descriptive nature of ‘instant Botox(R) alternative’, and (iv) inconsistent use of font, size, and presentation across different products and the user’s website.

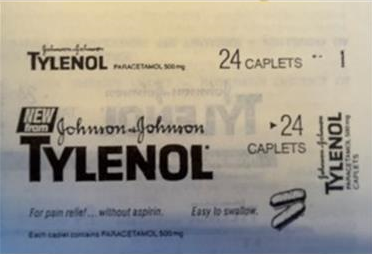

In Re Johnson and Johnson Australia Pty Limited v Stirling Pharmaceuticals Pty Limited [1991] FCA 310, an infringement action, the court considered whether use of the word CAPLETS on packaging for paracetamol was use ‘as a trade mark’. On the facts, the court held that there was no use ‘as a trade mark’. Relevant to the court’s decision was the fact that the word TYLENOL was the striking feature of the packaging and that the word CAPLETS was used in a similar sized font to clearly descriptive material (such as Paracetamol 500mg). Lockhart J held at 73:

On the facts, the court held that there was no use ‘as a trade mark’ by Johnson and Johnson. Relevant to the court’s decision was the fact that the word TYLENOL was the striking feature of the packaging and that the word CAPLETS was used in a similar sized font to clearly descriptive material (such as Paracetamol 500mg).

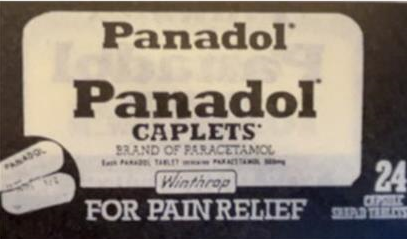

It is interesting to note that Sterling Pharmaceuticals (whose infringement action was unsuccessful) were presenting CAPLETS as a trade mark on their Panadol caplets packs (see the TM notation in the example below, indicating that Panadol Caplets is a "BRAND OF PARACETAMOL", with the word CAPLETS itself bearing a TM symbol) however,

Lockhart J held at [73]:

The context in which CAPLETS appears on the TYLENOL packaging and in its advertising demonstrates plainly in my opinion that the use is essentially descriptive and not a badge of origin in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between the product TYLENOL and the appellant. A person looking at the packaging would assume that the word CAPLETS describes or indicates the shape of the product contained in it or the dosage form. It is used in a descriptive sense precisely as the words tablets or capsules are used.

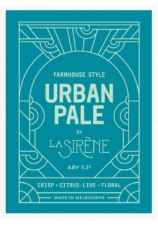

In Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirene Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82; 150 IPR 11(confirmed on appeal [2020] FCAFC 186), the court held at 204 that the dominant use of ‘Urban Pale’ on a beer label was as a product name descriptive of the nature and style of the beer product in question.

In reaching this conclusion, O’Bryan J took into account the nearby use of the words ‘by La Sirene’ which he considered conveyed the source of origin of the product.

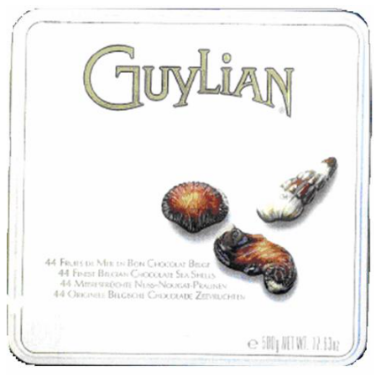

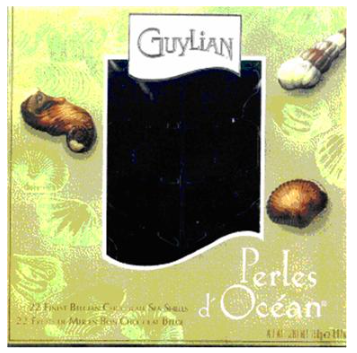

In Chocolaterie Guylian NV v Registrar of Trade Marks [2009] FCA 891, the applicant was seeking registration of a seahorse shape for chocolates. The applicant used the shape on chocolates that also displayed the letter ‘G’ prominently. The shape was also displayed on the front of a box that contained other ocean themed shapes and the mark GUYLIAN as its most striking feature.

In upholding the decision of the Registrar to refuse registration, Sundberg J said at [97]:

Each case turns on its own facts and here my impression of the packaging and promotional material as a whole is that it is the “Guylian” trademark, together with the “G” logo”, that does the work of distinguishing the goods, not the seahorse shape.

2.6 Summary of relevant considerations

A summary of some of the main considerations for determining whether use of a sign is use ‘as a trade mark’ is set out in the following table:

| Nature of sign | Note: |

| Is the sign invented or does it have some descriptive or laudatory significance? | An invented sign is more likely to be perceived as a trade mark than a sign with some descriptive significance. However, descriptive or laudatory terms can also be used as trade marks depending on the context. |

| Context of use | Note: |

| Is the sign displayed prominently in advertising, on displays, webpages or packaging or is it made less noticeable by being included amongst other material? | A sign that is used ‘as a trade mark’ will generally perform a ‘branding function’. It may be difficult for a person to show that a sign is performing a branding function where use of the trade mark appears to be intended solely for some descriptive or laudatory purpose. |

| Is it use of the trade mark as applied for? | Use of a sign that is not identical to the trade mark applied for can be considered if the additions or alterations do not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark (see 7). Use of a sign that is not substantially identical to the sign applied for may also be a relevant other circumstance that can be considered under s 41(4) and/or s 44(3)(b). |

| Has use been demonstrated in conjunction with, or close proximity to, other signs that are clearly acting as trade marks? | Use with other signs may indicate the sign is not being used as a trade mark in its own right. However, the use of multiple trade marks is common commercial practice and evidence should not be ignored simply because the trade mark applied for is not the only or most prominent trade mark used. The weight given to such evidence will depend on the circumstances of use. |

| Does the sign have a primarily functional purpose? | Functional features (e.g. on a shape trade mark) make it less likely (though not impossible) that a sign is acting as a badge of origin |

Amended Reasons

| Amended Reason | Date Amended |

|---|---|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

New updated to reference Henkel in part 19A.2.5 |

|

Adding image webpart |

|

Fixing images |

|

Added image webpart |

|

Images fixed. |

|

Images fixed. |

|

Content updated. |

|

Update hyperlinks |

|