- Home

- Part 1 Introduction, Quality

- Part 1. Introduction

- Part 1.2. Quality Management and Examination Quality Standards

- Part 1.3. Practice Change Procedure

- Part 2 General Filing Requirements

- Part 2. Landing Page

- Part 2.1. How a document is filed

- Part 2.2. Filing of Documents - requirements as to form

- Part 2.3. Non-compliance with filing requirements

- Part 2.4. Filing Process (excluding filing of applications for registration)

- Part 3 Filing Requirements for a Trade Mark Application

- Part 3. Relevant Legislation

- Part 3.1. Who may apply?

- Part 3.2. Form of the application

- Part 3.3. Information required in the application

- Part 3.4. When is an application taken to have been filed?

- Part 3.5. The minimum filing requirements

- Part 3.6. Consequences of non compliance with minimum filing requirements

- Part 3.7. Other filing requirements

- Part 3.8. Fees

- Part 3.9. Process procedures for non payment or underpayment of the appropriate fee

- Part 3.10. Process procedures for the filing of a trade mark application

- Part 4 Fees

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Fees - general

- 2. Circumstances in which fees are refunded or waived

- 3. Procedures for dealing with "fee" correspondence

- 4. Underpayments

- 5. Refunds and or waivers

- 6. No fee paid

- 7. Electronic transfers

- 8. Disputed credit card payments/Dishonoured cheques

- Part 5 Data Capture and Indexing

- Part 6 Expedited Examination

- Part 7 Withdrawal of Applications, Notices and Requests

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Withdrawal of an application, notice or request

- 2. Who can withdraw an application, notice or request?

- 3. Procedure for withdrawal of an application, notice or request

- 4. Procedure for withdrawal of an application to register a trade mark

- Part 8 Amalgamation (Linking) of Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Amalgamation of applications for Registration (Transitional)

- 2. Amalgamation (Linking) of Trade Marks under the Trade Marks Amendment Act 2006

- Part 9 Amendments and Changes to Name and Address

- Part 9. Landing Page

- Part 9. 1. Introduction

- Part 9. 2. Amendment of an application for a registration of a trade mark - general information

- Part 9. 3. Amendment before particulars of an application are published (Section 64)

- Part 9. 4. Amendment after particulars of an application have been published (Sections 63, 65 and 65A)

- Part 9. 5. Amendments to other documents

- Part 9. 6. Amendments after registration

- Part 9. 7. Changes of name, address and address for service

- Part 9. 8. Process for amendments under subsection 63(1)

- Part 10 Details of Formality Requirements

- Relevant Legislation

- Introduction

- 1. Formality requirements - Name

- 2. Formality requirements - Identity

- 3. Representation of the Trade Mark - General

- 4. Translation/transliteration of Non-English words and non-Roman characters

- 5. Specification of goods and/or services

- 6. Address for service

- 7. Signature

- 8. Complying with formality requirements

- Annex A1 - Abbreviations of types of companies recognised as bodies corporate

- Annex A2 - Identity of the applicant

- Part 11 Convention Applications

- Part 11. Landing Page

- Part 11.1. Applications in Australia (convention applications) where the applicant claims a right of priority

- Part 11.2. Making a claim for priority

- Part 11.3. Examination of applications claiming convention priority

- Part 11.4. Convention documents

- Part 11.5. Cases where multiple priority dates apply

- Part 11.6. Recording the claim

- Part 11.7. Effect on registration of a claim for priority based on an earlier application

- Part 12 Divisional Applications

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Divisional applications - general

- 2. Why file a divisional application?

- 3. Conditions for a valid divisional application filed on or after 27 March 2007

- 4. In whose name may a divisional application be filed?

- 5. Convention claims and divisional applications

- 6. Can a divisional application be based on a parent application which is itself a divisional application? What is the filing date in this situation?

- 7. Can the divisional details be deleted from a valid divisional application?

- 8. Divisional applications and late citations - additional fifteen months

- 9. Divisional Applications and the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012

- Annex A1 Divisional Checklist

- Part 13 Application to Register a Series of Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Series of Trade Marks - Act

- 2. Material Particulars

- 3. Provisions of Paragraphs 51(1)(a),(b) and (c)

- 4. Applying Requirements for Material Particulars and Provisions of Paragraphs 51(1)(a), (b) and (c)

- 5. Restrict to Accord

- 6. Examples of Valid Series Trade Marks

- 7. Examples of Invalid Series Trade Marks

- 8. Divisional Applications from Series

- 9. Linking of Series Applications

- 10. Colour Endorsements

- Part 14 Classification of Goods and Services

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. The purpose of classification

- 2. The classification system

- 3. Requirement for a clear specification and for correct classification

- 4. Classification procedures in examination

- 5. Principles of classification and finding the correct class for specific items

- 6. Wording of the specification

- 7. Interpretation of specifications

- 8. International Convention Documents

- Annex A1 - History of the classification system

- Annex A2 - Principles of classification

- Annex A3 - Registered words which are not acceptable in specifications of goods and services

- Annex A4 - Searching the NICE classification

- Annex A5 - Using the Trade Marks Classification Search

- Annex A6 - Cross search classes - pre-June 2000

- Annex A7 - Cross search classes - June 2000 to December 2001

- Annex A8 - Cross search classes from 1 January 2002

- Annex A9 - Cross search classes from November 2005

- Annex A10 - Cross search classes from March 2007

- Annex A11 - Cross search classes from January 2012

- Annex A12 - Cross search classes from January 2015

- Annex A13 - List of terms too broad for classification

- Part 15 General Provision for Extensions of Time

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. When the general provision applies

- 2. When the general provision does not apply

- 3. Circumstances in which the Registrar must extend time

- 4. Grounds on which the Registrar may grant an extension of time

- 5. Form of the application

- 6. Extensions of time of more than three months

- 7. Review of the Registrar's decision

- Part 16 Time Limits for Acceptance of an Application for Registration

- Part 16. Landing Page

- Part 16.1. What are the time limits for acceptance of an application to register a trade mark?

- Part 16.2. Response to an examination report received within four (or less) weeks of lapsing date

- Part 17 Deferment of Acceptance

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Deferment of Acceptance - introduction

- 2. Circumstances under which deferments will be granted

- 3. Period of deferment and termination

- 4. The deferment process where the applicant has requested deferment

- 5. The deferment process where the Registrar may grant deferment on his or her own initiative

- Annex A1 - Deferment of acceptance date - Grounds and time limits

- Part 18 Finalisation of Application for Registration

- Part 18. Landing Page

- Part 18.1. Introduction

- Part 18.2. Accepting an application for registration

- Part 18.3. Rejection of an application for registration

- Part 19A Use of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Use of a trade mark generally

- 2. Use 'as a trade mark'

- 3. Use 'in the course of trade'

- 4. Australian Use

- 5. Use 'in relation to goods or services'

- 6. Use by the trade mark owner, predecessor in title or an authorised user

- 7. Use of a trade mark with additions or alterations

- 8. Use of multiple trade marks

- Part 19B Rights Given by Registration of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. The trade mark as property

- 2. What rights are given by trade mark registration?

- 3. Rights of an authorised user of a registered trade mark

- 4. The right to take infringement action

- 5. Loss of exclusive rights

- Part 20 Definition of a Trade Mark and Presumption of Registrability

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Definition of a trade mark

- 2. Background to definition of a trade mark

- 3. Definition of sign

- 4. Presumption of registrability

- 5. Grounds for rejection and the presumption of registrability

- Part 21 Non-traditional Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Non-traditional signs

- 2. Representing non-traditional signs

- 3. Shape (three-dimensional) trade marks

- 4. Colour and coloured trade marks

- 5. "Sensory" trade marks - sounds and scents

- 6. Sound (auditory) trade marks

- 7. Scent trade marks

- 8. Composite trade marks - combinations of shapes, colours, words etc

- 9. Moving images, holograms and gestures

- 10. Other kinds of non-traditional signs

- Part 22 Section 41 - Capable of Distinguishing

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Registrability under section 41 of the Trade Marks Act 1995

- 2. Presumption of registrability

- 3. Inherent adaptation to distinguish

- 4. Trade marks considered sufficiently inherently capable of distinguishing

- 5. Trade marks that have limited inherent capacity to distinguish but are not prima facie capable of distinguishing

- 6. Trade marks having no inherent adaptation to distinguish

- 7. Examination

- Registrability of Various Kinds of Signs

- 8. Letters

- 9. Words

- 10. Phonetic equivalents, misspellings and combinations of known words

- 11. Words in Languages other than English

- 12. Slogans, phrases and multiple words

- 13. Common formats for trade marks

- 14. New terminology and "fashionable" words

- 15. Geographical names

- 16. Surnames

- 17. Name of a person

- 18. Summary of examination practice in relation to names

- 19. Corporate names

- 20. Titles of well known books, novels, stories, plays, films, stage shows, songs and musical works

- 21. Titles of other books or media

- 22. Numerals

- 23. Combinations of letters and numerals

- 24. Trade marks for pharmaceutical or veterinary substances

- 25. Devices

- 26. Composite trade marks

- 27. Trade marks that include plant varietal name

- Annex A1 Section 41 prior to Raising the Bar

- Annex A2 Flowchart of "Capable of Distinguishing"

- Part 23 Overcoming Grounds for Rejection under Section 41 - including Evidence of Use

- Part 23. Landing Page

- Part 23.1. Introduction

- Part 23.2 Submissions in rebuttal, amendments and informal information

- Part 23.3 Evidence of use - general requirements

- Part 23.4 Examining evidence - general

- Part 23.5 Specific evidence requirements for trade marks with no inherent adaptation to distinguish

- Part 23.6 Endorsements for applications overcoming section 41 grounds for rejection

- Part 23. Annex A1 - Information for applicants on the preparation and presentation of a declaration including model layout

- Part 23. Annex A2 - Model layout for statutory declaration/affidavit

- Part 23. Annex A3 - Model layout for supporting statutory declaration

- Annex A4 - How to supply evidence of use of a Trade Mark under subsection 41(5) - for trade marks with a filing date prior to 15 April 2013

- Annex A5 - How to supply evidence for use of a Trade Mark under subsection 41(6) - for trade marks with a filing date prior to 15 April 2013

- Annex A6 - How to supply evidence of use of a trade mark under subsection 41(4) - for trade marks with a filing date on or after 15 April 2013

- Annex A7 - How to supply evidence of use of a trade mark under subsection 41(3) - for trade marks with a filing date on or after 15 April 2013

- Part 24 Disclaimers

- Part 24. Landing Page

- Part 24.1. What is a disclaimer?

- Part 24.2. Request for a voluntary disclaimer

- Part 24.3. Effect of a disclaimer on registration

- Part 24.4. Effect of a disclaimer on examination

- Part 24.5. Amendment of disclaimers

- Part 24.6. Revocation of disclaimers

- Part 26 Section 44 and Regulation 4.15A - Conflict with Other Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction to section 44 and regulation 4.15A

- 2. Presumption of registrability and the application of section 44

- 3. Cross Class Search List

- 4. Similarity of goods and services

- 5. Similarity of trade marks

- 6. Factors to consider when comparing trade marks

- 7. Trade marks with the same priority/filing date

- 8. Assignment of applications and registrations

- 9. Grounds for rejection when the citation is in its renewal period

- Annex A1 - Citing multiple names

- Part 27 Overcoming Grounds for Rejection under Section 44

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 3. Amending the goods and/or services of the applicant's specification

- 4. Negotiation with owner/s of conflicting trade mark/s

- 5. Filing evidence of honest concurrent use, prior use or other circumstances

- 6. Removal of the conflicting trade mark

- 7. Dividing the application

- Annex A1 - An example of a letter of consent

- 2. Legal submissions

- Part 28 Honest Concurrent Use, Prior Use or Other Circumstances

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Honest concurrent use - paragraph 44(3)(a)

- 3. Examining evidence of honest concurrent use - the five criteria

- 4. Other circumstances - paragraph 44(3)(b)

- 5. Conditions and limitations to applications proceeding under subsection 44(3)

- 6. Prior use - subsection 44(4)

- 7. Examining evidence of prior use

- 8. Endorsements where the provisions of subsection 44(3) or 44(4) and/or reg 4.15A are applied

- Annex A1 - Information sheet for trade mark applicants - Evidence of honest and concurrent, prior use or other circumstances

- Part 29 Section 43 - Trade Marks likely to Deceive or Cause Confusion

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Trade marks likely to deceive or cause confusion

- 2. Connotation

- 3. Deception and confusion as a result of a connotation within a trade mark

- 4. Descriptions of goods/services

- 5. International Non-Proprietary Names and INN Stems

- 6. Names of Persons

- 7. Phonewords and Phone Numbers

- 8. Internet Domain Names

- 9. Geographical References

- 10. Claims to Indigenous Origin

- Annex A1 - Table of INN stems

- Part 30 Signs that are Scandalous and Use Contrary to Law

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Scandalous signs

- 3. Use contrary to law

- Annex A1 - Examples of Legislation which may trigger the provisions of section 42(b)

- Annex A2 - Official notice re copyright in the Aboriginal Flag

- Annex A3 - Defence force prohibited terms and emblems

- Annex A4 - Major Sporting Events protected words

- Annex A5 - Examples regarding Geneva Conventions Act 1957 s 15(1)

- Part 31 Prescribed and Prohibited Signs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Prohibited signs - subsection 39(1)

- 2. Prescribed signs - subsection 39(2)

- 3. When does a ground for rejection exist under subsection 39(2)?

- 4. Practice regarding the signs prescribed under subsection 39(2) appearing in subreg 4.15

- 5. Other information relevant to examining trade marks that contain a prohibited and prescribed sign

- Part 32A Examination of Trade Marks for Plants (in Class 31)

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Examination of Plant Trade Marks

- 2.1 Section 42: Contrary to Law

- 2.2 Section 39: Prescribed Signs

- 2.3 Section 41: Capacity to Distinguish

- 2.4 Section 43: Deception and Confusion

- 2.5 Section 44: Comparison of Trade Marks

- 2.6 Non-Roman characters (NRC) and transliterations in class 31 plant examination

- Annex 1 - Applicable Section of the PBR Act

- Annex 2 - Applicable Sections of the UPOV Convention

- Annex 3 - Applicable Sections of the ICNCP

- Annex 4 - An Example of a PBR Letter of Consent

- Annex 5 - Case Law Summaries

- Annex 6 - How to Supply Evidence of Use of a Trade Mark for Plants and/or Plant Material

- Part 32B Examination of Trade Marks for Wines (in Class 33)

- Part 32B: Landing Page

- Part 32B.1. Introduction

- Part 32B.2. Examination of Wine Trade Marks

- Part 32B.2.1 Section 42: Contrary to Law

- Part 32B.2.2 Section 43: Deception and Confusion

- Part 32B.2.3 Section 41: Capacity to Distinguish

- Part 32B.2.4 Section 44: Comparison of Trade Marks

- Part 32B.3. Protected Terms in Specifications of Goods

- Part 33 Collective Trade Marks

- Part 33. Landing Page

- Part 33.1. What is a collective trademark?

- Part 33.2. Application of Act

- Part 33.3. Application for registration

- Part 33.4. Limitation on rights given by registered collective trade marks

- Part 33.5. Assignment or transmission of collective trade marks

- Part 33.6. Infringement of collective trade marks

- Part 34 Defensive Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Australian trade marks law and defensive trade marks

- 2. Requirements for the filing of a defensive trade mark

- 3. Section of the Act NOT applying to defensive trade marks

- 4. Registrability of defensive trade marks

- 5. Grounds for rejection under Division 2 of Part 4 of the Act

- 6. Grounds for rejecting a defensive application under section 187

- 7. Evidence required for defensive applications

- 8. Rights given by defensive registration

- 9. Grounds for opposing a defensive registration

- 10. Cancellation of defensive trade marks

- Part 35 Certification Trade Marks

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is a certification trade mark?

- 2. Certification trade marks and geographical indications (GIs)

- 3. Sections of the Act NOT applying to certification trade marks

- 4. The registrability of certification trade marks

- 5. Rights given by, and rules governing the use of, certification trade marks

- 6. Assessment by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)

- 7. Opposition to the registration of a certification trade mark

- 8. Variation of rules

- 9. Assignment of registered certification trade marks

- 10. Assignment of unregistered certification trade marks

- 11. Transmission of certification trade marks

- 12. Rectification of the Register and variation of rules by order of the court

- Annex A1 - Certification Trade Marks flow chart

- Part 38 Revocation of Acceptance

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is revocation of acceptance?

- 2. Reasons for revocation

- 3. Revocation process

- Part 39 Registration of a Trade Mark

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Overview of registration

- 2. Particulars of registration

- 3. Format of Certificate of registration

- 4. Timing

- 5. Date and term of registration

- 6. Registration fees

- 7. Registration process

- 8. Notification of Protection process for International Registrations Designating Australia

- Annex A1 - Certificate of Registration

- Part 40 Renewal of Registration

- Part 40. Landing Page

- Part 40.1. What is renewal?

- Part 40.2. Timing for renewal

- Part 40.3. Late renewal

- Part 40.4. Failure to renew

- Part 41 Cancellation of Registration

- Part 41. Landing Page

- Part 41.1. What is the effect of cancelling a registration?

- Part 41.2. Why is a registration cancelled?

- Part 41.3. Cancellation process

- Part 42 Rectification of the Register

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is rectification?

- 2. What part does the Registrar play in rectification actions brought by a person aggrieved?

- 3. Rectification procedures

- Annex A1 - Flow chart of rectification procedure

- Part 43 Assignment and Transmission

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is assignment and transmission?

- 2. Timing for assignment

- 3. Application to record assignment etc

- 4. Process for assigning all goods and/or services (full assignment)

- 5. Process for assigning only some goods and/or services (partial assignment)

- 6. Process for assignment of certification trade marks

- 7. Transmission of certification trade marks

- Part 44 Claim of Interest or Rights in a Trade Mark

- Part 44. Landing Page

- Part 44.1. Background

- Part 44.2. Effect of recording the claim

- Part 44.3. When can the interest be recorded?

- Part 44.4. Recording the claim

- Part 44.5. Amending the record of a claim

- Part 44.6. Cancelling the record of a claim

- Part 45 Copies of Documents

- Part 45. Landing Page

- Part 45.1. Documents copied by the Office

- Part 45.2. Types of document copies and delivery dispatch

- Annex A1 - Flow chart of production of copies/certified copies

- Part 46 Grounds for Opposition to Registration or Protection

- Relevant Legislation

- References used in this part

- 1. What is opposition to registration or protection?

- 2. The Registrar’s role in an opposition

- 3. When registration or protection can be opposed

- 4. Grounds for opposition to registration of national trade marks

- 5. Grounds for opposition to protection of international trade marks

- Part 47 Procedures for Opposing Registration or Protection

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Filing a notice of opposition

- 2. Request to amend a notice of intention to oppose or a statement of grounds and particulars

- 3. Filing a notice of intention to defend

- 4. Opposition may proceed in the name of another person

- 5. Making Convention documents available to opponent

- Part 48 Removal of a Trade Mark from the Register for Non-use

- Relevant legislation

- References used in this part

- 1. What if a trade mark is not used?

- 2. Application for removal/cessation of protection for non-use

- 3. Opposition to a non-use application

- 4. Application for extension of time to oppose the non-use application where the trade mark is already removed

- 5. Grounds on which a non-use application may be made

- 6. Burden on opponent to establish use of a trade mark

- 7. Authorised use by another person

- 8. Use by an assignee

- 9. Localised use of trade mark

- 10. Circumstances that were an obstacle to the use of a trade mark

- 11. Where there is no evidence in support of the opposition

- 12. Registrar's discretion in deciding an opposed non-use application

- 13. Registrar to comply with order of court

- 14. Right of appeal

- 15. Certificate - Use of a trade mark

- Part 49 Non-use Procedures

- Relevant legislation

- 1. Application for removal or cessation of protection of a trade mark for non-use

- 2. Opposition to non-use application

- 3. Amendment to notice of intention to oppose or statement of grounds and particulars

- 4. Notice of intention to defend

- 5. Opposition may proceed in the name of another person

- 6. Opposition proceedings

- Part 51 General Opposition Proceedings

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Evidence

- 2. Extension of the period for filing evidence

- 3. Cooling-Off Period

- 4. Suspensions

- 5. Hearing of the opposition

- 6. Dismissal or discontinuance of proceedings

- 7. Award of costs

- 8. Rights of appeal

- 9. Period in which a trade mark can be registered/protected

- 10. Guidelines for Revocation of Acceptance of Opposed trade marks

- 11. Unilateral Communications with Hearing Officers

- Part 52 Hearings, Decisions, Reasons and Appeals

- Relevant Legislation

- References used in this Part

- 1. What is a decision?

- 2. What is a hearing?

- 3. Is a hearing always necessary?

- 4. Role and powers of the Registrar in hearings

- 5. Rights of appeal from decisions of the Registrar

- 6. Appeals from decisions of the Federal Court etc.

- 7. Implementation of decisions

- 8. Service of documents on the Registrar

- Part 54 Subpoenas, Summonses and Production of Documents

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Subpoenas

- 2. Summonsing a witness

- 3. Production of documents

- Annex A1 - Consequences of mishandling a subpoena

- Annex A2 - Format of a summons to witness

- Annex A3 - Format of notice requiring production

- Part 55 Costs

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Legislative Basis

- 2. Award of costs

- 3. Applications for an award of costs

- 4. Determination of the amount of costs

- 5. Full costs where certificate of use of a trade mark provided to removal applicant

- 6. Costs recovery

- 7. Security for costs

- Annex A1 - Taxing of costs in "multiple" oppositions relying on same evidence

- Part 60 The Madrid Protocol

- Relevant Legislation

- Glossary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. International Applications

- 2.1 General Description

- 2.2 International Application Form

- 2.3 Data Entry

- 2.4 Certifying Process

- 2.5 Fees for International Applications

- 2.6 Renewal

- 3. The Basic Application or Basic Registration (Basic Trade Mark)

- 4. International Registrations that have Designated Australia

- 4.1 General Description

- 4.2 Record of International Registrations

- 4.3 Filing/Data Capture/Allocation of Australian Trade Mark Number

- 4.4 Indexing

- 4.5 Expedite

- 4.6 Classification of Goods and Services

- 4.7 Examination of an IRDA

- 4.8 Reporting on an IRDA

- 4.9 Provisional Refusal

- 4.10 Amendments

- 4.11 Deferment of Acceptance

- 4.12 Extension of Time

- 4.13 Final Decision on Provisional Refusal Based on Examination

- 4.14 Acceptance

- 4.15 Revocation of Acceptance

- 4.16 Extension of Time to File Notice of Opposition to Protection

- 4.17 Opposition to Protection

- 4.18 Protection

- 4.19 Cessation or Limitation of Protection

- 4.20 Cessation of Protection because of Non-Use

- 4.21 Opposition to Cessation of Protection because of Non-Use

- 4.22 Renewal

- 4.23 Claim to Interest in, or Right in Respect of a Trade Mark

- 4.24 Change in Ownership of an International Registration

- 4.25 Transformation

- 4.26 Replacement

- 4.27 Customs

- Part 61 Availability of Documents

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. Availability of Documents

- 2. Accessing Documents

- 3. Documents to be made Available for Public Inspection (API)

- 4. Information that the Registrar of Trade Marks will Not Accept in Confidence

- 5. Confidential Information in Correspondence

- 6. Policy in relation to TM Headstart

- Part 62 Revocation of Registration

- Relevant Legislation

- 1. What is revocation of registration?

- 2. Prerequisites to revocation of registration

- 3. Factors to be taken into account before deciding whether revocation of registration is reasonable

- 4. Circumstances under which registration may be revoked

- 5. Mandatory revocation

- 6. Right of appeal: revocation of registration

- 7. Extension of time

- 8. Amendment or cessation of protection by Registrar of Protected International Trade Marks (PITMs)

- 9. Registrar must notify Customs if protection of a PITM is revoked

- 10. Right of appeal: cessation of protection

26.6. Factors to consider when comparing trade marks

The following principles have been developed over many years from the case law and decisions of the Registrar. In each case, the nature of the trade marks will determine the criteria which will be most appropriate to determine whether they are deceptively similar.

6.1 Sound as well as appearance to be considered

In determining the resemblance between two trade marks, the possibility of slurred pronunciation, distortion of sound in telephone or other conversations and the syllabic structure of words must be taken into account. On the question of the “sound” of a trade mark, reference can be made to the words of Sargant LJ in the “ Tripcastroid” case, London Lubricants (1920) Limited's Application (1924) 42 RPC 264 at 279:

The only similarity in the word “ Tripcastroid” to “ Castrol” is in the letters composing the centre of the new word. The termination of the new word is different. Though I agree that, if it were the only difference, having regard to the termination of words, that might not alone be sufficient distinction. But the tendency of persons using the English language to slur the termination of words also has the effect necessarily that the beginning of words is accentuated in comparison, and, in my judgement, the first syllable of a word is, as a rule, far the most important for the purpose of distinction.

This highlights the importance of the beginnings of the words being compared. In this regard see also:

Aristoc Limited v Rysta Limited(1943) 60 RPC 87 (Rysta), where the words RYSTA and ARISTOC were held not to be deceptively similar;

Enoch’s Application (1947) 64 RPC 119 (‘Cyllin’)where it was held VIVICILLIN and CYLLIN were not deceptively similar;

Bayer’s Application (1947) 64 RPC 125 where DIASIL and ALASIL were held to be not deceptively similar;

Magdalena Securities (1931) 48 RPC 477 (Ucolite)where it was held UCOLITE and COALITE were deceptively similar.

Clipsal Australia Pty Ltd v Clipso Electrical Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 60 where it was held that CLIPSAL and CLIPSO were deceptively similar;

Combe International Ltd v Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co. KG Arzneimittel [2021] FCAFC 8 (‘Vagisil’) where it was held that VAGISAN and VAGISIL were deceptively similar;

However, the findings of the above cases should be considered in the light of contemporary marketing methods. The Hearing Officer in Giorgio Armani S.p.A v Tiawan Yamani (1989); 17 IPR 92 decided that:

...the opponents case...must fail because, in relation to the goods in question here, I regard the visual impact of the marks, which is very different, to be of more importance than any aural similarity. The commercial reality today is that articles of clothing are simply not purchased over the counter on a verbal request but are carefully selected by a potential customer from a rack in a shop and very carefully inspected and compared with similar articles

6.2 Imperfect recollection

In considering whether trade marks are deceptively similar, the House of Lords in the “ Rysta” case discussed the doctrine of imperfect recollection and the importance of first impression (1943) 60 RPC 87 at page 108:

The answer to the question of whether the sound of one word resembles too nearly the sound of another...must nearly always depend on the first impression, for obviously a person who is familiar with both words will neither be deceived nor confused. It is the person who only knows the one word, and has perhaps an imperfect recollection of it, who is likely to be deceived. Little assistance, therefore, is to be obtained from a meticulous comparison of the two words, letter by letter and syllable by syllable, pronounced with the clarity to be expected from a teacher of elocution.

The Court must be careful to make allowance for imperfect recollection and the effect of careless pronunciation and speech on the part not only of the person seeking to buy under the trade description but also of the shop assistant ministering to that person's wants.

However, the House of Lords, also pointed out in Rysta that this factor must not be too strongly emphasised. Lord Greene MR at 105:

The doctrine of imperfect recollection must not be carried too far. In considering its application not only must the class of person likely to be affected be considered, but no more than ordinary possibilities of bad elocution, careless hearing or defective memory ought to be assumed.

In this regard see also:

Broadhead’s Application , (1950) 67 RPC 113 (‘Alkaseltzer’) where it was held that ALKA-SELTZER and ALKA-VESCENT were similar when used in relation to seltzer water; and

In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 193 where it was held that IN-N-OUT BURGER was similar to DOWN/D#WN N’ OUT. This decision was upheld on appeal.

6.3 The 'idea' of the trade mark

Although the two trade marks under consideration may contain many differences, a ground for rejection under section 44 could apply if they did in fact convey the same idea. (See Jafferjee v Scarlett [1937] HCA 36(‘Jafferjee’). Some trade marks which have features in common are seen to be different when viewed side by side. However, if the same idea is engendered by both trade marks and it is thought that some purchasers are likely to remember the trade marks by the idea rather than by the specific visual or aural features of the trade marks, use of the trade marks may lead to confusion. Grounds for rejection may then exist under s 44 on the basis of deceptive similarity of the trade marks.

When considering a ground for rejection based on the trade marks conveying a similar idea, the sound and/or look of the trade marks should be taken into account (Sports Café Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks [1998] FCA 1614 (‘Sports Café’)). This however does not mean that the idea that trade marks convey are only taken into account once visual or aural similarity is established, nor that visual and aural features do not need to be strongly considered if trade marks do in fact convey the same idea or concept. This is discussed in Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd (2015) FCAFC 156 (Yellow), which includes references to both the Sports Café and Cooper Engineering Company Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Limited [1952] HCA 15 (Rainmaster) decisions – see 210 and 211. In Yellow at the court said at [212]:

The takeaway from this case is that the commonality of idea is part of the process of determining if the marks look or sound alike

The idea that a trade mark evokes is an important factor to consider when establishing the visual and aural features a consumer is likely to pay attention to and recollect. A holistic visual, aural, and conceptual assessment should be undertaken to establish the general overall impression that exists when comparing trade marks.

In Dial An Angel Pty Ltd v Sagitaur Services Systems Pty Ltd [1990] FCA 312, Wilcox J held that while the words DIAL-AN-ANGEL and GUARDIAN ANGEL were not deceptively similar, the associated logos which each contained a representation of an angel with children, although different in detail, were considered to be deceptively similar as a result of “the idea of the mark” and the similar impression created by them.

DIAL-AN-ANGEL versus GUARDIAN ANGEL

See also:

De Cordova v Vick Chemical Co,. (“VapoRub” case) (1951) 68 RPC 103 in which VAPORUB was held to be similar to KARSOTE VAPOUR RUB;

Rainmaster where RAINMASTER was held to be sufficiently different to RAIN KING.

6.4 Trade marks that share the same or similar element

Some of the more difficult section 44 considerations involve two trade marks sharing the same element (or elements that are very similar). However, the same general principles apply when considering deceptive similarity in such cases. In particular, in evaluating the likelihood of confusion, the marks must be judged as a whole: Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15, at [3].

It is important that examiners do not default to a finding that two trade marks are deceptively similar merely because one trade mark is wholly encompassed within the other. While that is a relevant consideration, it is not of itself determinative.

While a real and tangible danger of confusion can arise if one mark is contained in another, the existence of a common element is not sufficient to conclude the marks are deceptively similar. What needs to be assessed is the effect of the similarities and differences on the impression or recollection an ordinary consumer of the goods or services would have of the trade marks and whether this creates a real and tangible danger of confusion.

When assessing the likelihood of confusion between the impressions created by trade marks that share the same element/s, the examiner should consider:

| Trade Marks | Deceptively similar or Substantially Identical | |

|---|---|---|

MOTHER v MOTHERSKY | Yes |

The extent to which the shared element has retained its identity as an essential feature of the trade marks (Bulova Accutron Trade Mark [1969] RPC 102). In Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 44 at [167-171], the court held that MOTHER and MOTHERSKY were deceptively similar. In doing so, the Court took into account the fact the word MOTHER is wholly incorporated in MOTHERSKY, the dominating element of MOTHERSKY is the word MOTHER, the word SKY is not likely to have a well-understood meaning when combined with MOTHER, and the word MOTHER does not lose its identity by the addition of the suffix SKY. However, the court first found that the word MOTHER is not in any way descriptive of non-alcoholic beverages (and therefore inherently distinctive when used in respect of those goods) and expressly noted this distinctiveness was “of considerable importance to [their] assessment”. As such, examiners should not deem two trade marks to be deceptively similar simply because they share element/s. Examiners must first consider the other factors referred to in this Part, including whether the shared element/s have any descriptive meaning in relation to the relevant goods/services. Further, it is important that a single word or element is not too readily characterised as an essential feature (Crazy Ron's Communications Pty Limited v Mobileworld Communications Pty Limited [2004] FCAFC 196, at [100]) (Crazy Ron’s). |

JESTS v EASYJEST

v PROCAT | Yes | Whether because of the shared element consumers might think that the one mark is a variant, sub-brand, commercial extension, or related to another trade mark even though the differences between them would be readily apparent to consumers: In the Matter of John Fitton & Co Limited’s Application (1949) 66 RPC 110 (JESTS and EASYJEST) and Caterpillar Inc v Puma SE [2021] FCA 1014 (CAT and PROCAT). Examiners should carefully consider whether the additional element/s give rise to this risk in the context of the relevant goods/services. For example, in the Caterpillar decision, the court considered that, in the context of the relevant goods (apparel, footwear, bags and accessories), there was a real and tangible risk that a significant number of consumers would be confused into thinking that goods labelled with PROCAT were a ‘professional’ or high performance line of CAT goods. |

MONSOL v MULSOL | No | Whether the shared element has been used by a number of traders and should to some extent be discounted: Mond Staffordshire Refinery Co Ltd v Harlem [1929] HCA 6; (1929) 41 CLR 475 at 477–8; Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co [1994] FCA 1001; (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 127; MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd [1998] FCAFC 1616;connect.com.au Pty Ltd v GoConnect Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1148. In the Mond Staffordshire case, in finding that consumers were not likely to be confused between the Mulsol and Monsol trade marks, the High Court took into account that a number of trade marks ending in “sol” and “ol” and beginning with “mul” had been registered as trade marks and used in Australia. |

v BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE | No | The distinctiveness of the common element/s. In Bed Bath ‘N’ Table PL v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC HOUSE BED & BATH were found to be sufficiently different to BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE due to the prominence of the word ‘House’ and the descriptive character of the words ‘BED & BATH’. In Swancom Pty Ltd v The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 328 (at [239]) JAZZ CORNER HOTEL and CORNER HOTEL were considered not to be deceptively similar. Similarly, in The Agency Group Australia Limited v H.A.S. Real Estate Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 482, THE AGENCY (stylised) and THE NORTH AGENCY were not considered deceptively similar for real estate services, Jackman J finding (at [72]) that "The ordinary consumer would expect the word “agency” to be commonly used in the names of real estate businesses in Australia. It would give an unwarranted monopoly to The Agency Group if rival businesses were unable to use the definite article “The” and the word “Agency” in their business names. The ordinary consumer would not be confused by the fact that those words have been used by a rival trader, in light of their relatively high degree of descriptiveness of the nature of the business.” |

THE NORTH AGENCY v  | No | |

BRATS v BONZA BRATS | Yes | The nature of the additional element(s) – if the additional element(s) is/are particularly distinctive and sufficiently alter the impression of the mark as a whole then the marks may not be deceptively similar, even though they share a common element. And vice versa – if the additional element has a low level of distinctiveness, then the marks are more likely to be deceptively similar (Application by Coles Myer Ltd, (1993) 26 IPR 577, comparing BRATS and BONZA BRATS). |

MERCATO v MERCATO CENTRALE and

| Yes | Whether consumers are likely to perceive elements of a trade mark as descriptive additions due to the nature of those elements, including taking into account common conventions such as where descriptive adjectives follow nouns to indicate a variant or sub-brand: Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 156 at [155]-[157]. In the Mercato Centrale decision, the Full Court found that the plain words MERCATO CENTRALE and IL MERCATO CENTRALE were deceptively similar to a plain word registration for MERCATO, and took into account that “it is common knowledge that descriptive adjectives may follow nouns in the particular context of sub-brands, often to indicate a variant of some description. Well-known examples include Coke Zero, Pepsi Max, Virgin Mobile, Coles Local, MacBook Pro, Samsung Galaxy Ultra, and Nescafe Gold”. However, the Full Court found that the plain words MERCATO CENTRALE and IL MERCATO CENTRALE were not deceptively similar to a registration for the stylised word because an essential feature of that registration is that “it is in a fancy script. The monopoly it secures is not a monopoly over the plain word mercato. Rather, it secures a monopoly over that word as rendered in the fancy script depicted on the Register” and “the notional consumer’s imperfect recollection […] would, as part of that imperfect recollection, include that the word is rendered in a curly typeface”. |

v MERCATO CENTRALE and

| No | |

v

| No | The meaning behind the trade marks – where an additional element changes the meaning of the trade mark or the concept behind it then the trade marks are less likely to be deceptively similar. In PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1078 at [177] to [200] the court held that in the trade mark WICKED SISTER, neither WICKED nor SISTER were the clear essential feature of the mark, and as a whole, WICKED SISTER was not deceptively similar to WICKED in slightly stylised form. |

v

| No | The placement, within the trade mark, of the common and non-distinctive elements, including size of text and any other elements may provide a different context and consequently alter the overall impression of the trade mark. See REA Group Ltd v Real Estate 1 Ltd [2013] FCA 559 in which the following trade marks were compared |

BAREFOOT V BAREFOOT RADLER | Yes | When both the common element and additional element are distinctive – each case will turn on its own facts. See E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Limited [2008] FCA 934 at [63] per Flick J. |

Decisions of the Registrar also provide some guidance:

Marks being compared | Decision | Reasons/Quote |

Eau De Cologne’s Application (1990)17 IPR 540 MY MELODY DREAMS VS MY MELODY | Deceptively Similar | Reasons for this decision include that the impression created is that ‘goods bearing the trade marks are different products in the same product range from the one trade source’ at 542. |

Re Application by Coles Myer Ltd (1993) 26 IPR 577 BRATS VS BONZA BRATS | Deceptively Similar | Reasons for this decision include that the word BONZA is a widely known colloquialism which acts solely as a qualifier of the word BRATS in the trade mark BONZA BRATS at 579. |

Jockey International, Inc v Darren Wilkinson [2010] ATMO 22 JOCKEY VS THROTTLE JOCKEY | Sufficiently Different | Reasons for this decision include that ‘THROTTLE JOCKEY gave rise to an entirely different connotation, construction and interpretation than the word JOCKEY’ at 39. |

Chris Kingsley v David Scott [2011] ATMO 20 REBELLION VS SOUL REBELLION | Sufficiently Different | Reasons for this decision include that 'SOUL REBELLION has an ordinary dictionary meaning which is unlikely to be confused or associated with the word REBELLION by itself' at 15. |

6.5 Reputation or notoriety of a mark

An enquiry under s 44 should not take into account reputation in any element of either trade mark under comparison. The assessment of whether two marks are deceptively similar is confined to a comparison of their particulars and the uses to which the marks might be properly put. In Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd(Protox) [2023] HCA 8 the High Court said [at 36]:

In support of those contentions, the amicae principally relied on three authorities that considered the issue of reputation – Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd, CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd and Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd v JBS Australia Pty Ltd – and from which a "principle" that reputation is relevant where it lessens the risk of "imperfect recollection" in the assessment of deceptive similarity under s 120(1) of the TM Act was said to be drawn. It will be necessary to consider each of these authorities below because, as will be explained, all forms of any socalled principle should be rejected. Reputation should not be taken into account when assessing deceptive similarity under s 120(1). That conclusion is compelled by the structure and purpose of, and the fundamental principles underpinning, the TM Act. (emphasis in original)

Sections 44 and 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) involve the same inquiry for assessment of deceptive similarity (being the one provided by the High Court in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v F S Walton & Co Ltd [1937] HCA 51). As such, while the decision in Protox was made in the context of s 120, the reasoning is applicable to s 44.

Previously, the Federal Court in Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths [1999] FCA 1020 (Woolworths) held that where an element of a trade mark had a degree of notoriety or familiarity, this may be relevant to determining whether it was deceptively similar with another trade mark. The rationale for this principle being that the presence of an element with a very high degree of notoriety, such as was enjoyed by Woolworths for retail services, reduces the potential for imperfect recollection. This was explicitly rejected by the High Court’s findings in Protox, and is no longer the law.

Further, since the decision in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 156 [133] it is settled that the onus on a party seeking to assert deceptive similarity under s 44 for the purposes of opposition (or cancellation) is the same ordinary balance of probabilities as a plaintiff seeking to assert the same under s 120. Such commonality to approaching deceptive similarity only further emphasises that, regardless of the views held at the time of Woolworths, the principles relating to deceptive similarity must applied consistently to s 44, as they are applied to s 120.

The consistent interpretation of deceptive similarity in the context of s 44 and s 120 is also supported by the principle of statutory construction that ‘cognate expressions in a statue should be given the same meaning unless context requires a different result’ (Kline v Official Secretary to the Governor-General [2013] HCA 52 [32]).

6.6 Considering invented words

There is a much greater possibility of deception and confusion between words which are not in common use in the language. In William Bailey (Birmingham) Ltd.’s Appln. (1935) 52 RPC 136, Farwell J said at [153]:

No doubt in the case of a fancy or invented word, a word which is not in use in the English language, the possibility of confusion is very much greater. A fancy word is more easily carried in mind and is more easily carried in mind in connection with some particular goods and it may well be that in the case of a fancy word there is much more chance of confusion and therefore less evidence may be required to establish the probability of confusion in the case of a fancy word than in the case of a word in the English language.

This decision was cited with approval by Murphy J in Nexans S.A. v Nex 1 Technologies Co. Ltd [2012] FCA 180 at [31].

Similarities in invented words must be considered in context. For example, smaller in differences in short invented words may create more significant differences in overall impression, particularly where that difference occurs at the beginning of the mark. : For instance, in Opposition by FENDI PAOLA & S.LLE S.a.S to the registration of Trade Mark 473729 [1993] ATMO 26, Hearing Officer Farquhar said, in assessing trade marks JENDI against an earlier registration for FENDI:

It was found in London Lubricants (1920) Ltd's Appn (1925) 42 RPC 264 that the beginning of words is accentuated in comparison with the end of the word so that 'the first syllable of a word is, as a rule, far the most important for the purpose of distinction'. This was supported in "Fif" Trade Mark [1979] RPC 355 and also the finding in "Mem" Trade Mark [1965] RPC 347. In both of these cases, it must be noted, one of the conflicting marks had some meaning. The comments in London Lubricants supra are most applicable to polysyllabic words and I consider they are pertinent here. It is not necessary to pronounce a word to impress it on the memory. The form of the word will be noted and the beginning of the word will be what is impressed on the mind. There are two possibilities with these marks. It is likely the final 'i' will be overlooked as an insignificant ending, leaving in the memory the words FEND and JEND. I believe consumers would be unlikely to confuse these two. Alternatively if the last syllable is noted it is still unlikely that the two would be confused.

6.7 The descriptiveness of the trade mark

It is generally appropriate to pay less attention to non-distinctive matter when comparing marks. This is because non-distinctive matter is less likely to be taken as an indication of the origin of the goods or services, and consumers are therefore unlikely to be confused by the presence of similar, non-distinctive, matter in two or more trade marks. In Rainmaster the High Court had to consider whether the mark RAIN KING, registered in respect of ‘spray nozzles, sprinklers and their parts’, should block an application for the mark RAINMASTER for similar goods. In concluding that there was no reasonable likelihood of deception between the marks, the Court said at [3]:

A purchaser of spray nozzles and sprinklers…would not be likely to pay any attention to the presence of a common word like rain in the combination. That prefix already appears in other trademarks for goods of the same description sold on the Australian market such as Rainwell, Rainmaker, Rain Queen, and Rainbow. The learned registrar was right in holding that the only similarity between the two marks is the common prefix ‘Rain’ and that this similarity is not sufficient to create a reasonable likelihood of deception when the remaining portions of the marks are so different.

In Ucolite, Maugham J said at [486]:

I think it is true to say that when a registered trade mark...has a descriptive tinge the Courts are rather averse to allowing that fact to tend to become a kind of monopoly in respect to the descriptive character of the word.

The trade mark system is not intended to focus exclusively on eliminating all risk of consumer confusion, irrespective of the needs of other traders. A decision maker may have no choice but to tolerate some risk of confusion if a trader has chosen to build a business around a descriptive term and a later trader wishes to use that descriptive term in relation to its own business. This is to be seen in the decision of the High Court in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd [1978] HCA 11, dealing with the statutory consumer protection regime:

The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words…” (at p. 229 per Stephen J).

Hearing Officers have applied this principle in numerous decisions under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth): for example, LexiMed Pty Ltd v Lex Medicus Pty Ltd [2013] ATMO 63; Cars on Demand IP Pty Ltd v Cars on Demand Ltd [2014] ATMO 87; Combined Communications Pty Ltd v Combined Communication Solutions Pty Ltd [2014] ATMO 117; Australian Homestay Network Pty Ltd v Homestay Network Pty Ltd [2015] ATMO 28; Australian Ezy Tax Systems Pty Ltd v Ezy Tax Solutions Pty Ltd [2016] ATMO 62; Taronga Conservation Society Australia v Sydney Zoo Pty Ltd [2017] ATMO 155; Ng v Aussie Dazzling Life Pty Ltd [2018] ATMO 136; Capital Safety Group EMEA v Classic Supplies Pty Ltd [2019] ATMO 10.

It must, however, be stressed that this does not mean that descriptive matter is to be excluded when marks are being compared. As Hearing Officer Wilson noted in Australian Ezy Tax Systems Pty Ltd v Ezy Tax Solutions Pty Ltd [2016] ATMO 62 at [22]:

“A descriptive element within a trade mark may be to some extent discounted in a comparison (or to paraphrase Hornsby, a certain risk of confusion due to the presence of that element may be accepted), but those descriptive elements cannot be entirely ignored in the overall comparison.”

The consequence is that whether the common presence of descriptive matter will lead to a finding that the marks are deceptively similar will depend on the facts of the case at hand. Conclusions will vary depending on the precise marks at issue and the goods or services in question.

6.8 Descriptive words in composite marks

The question of what weight should be given to the common presence of non-distinctive words when assessing deceptive similarity often arises in cases involving composite marks. As explained in Part 22.26, composite marks that consist of a distinctive device and a non-distinctive word will generally be prima facie distinctive and registrable. The presence of the device will mean that consumers will immediately understand the mark to be a badge of origin and it is unlikely that other traders will need to use any such particular word-device combination. However, difficult questions can arise when word-device combinations are being compared with later marks that include the same non-distinctive word combined with a notably different device or with other distinctive matter.

The correct approach in such a case is to focus on the comparison of the marks as a whole. As the Full Federal Court warned in Crazy Ron's Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 196 (‘Crazy Ron’s) at [100]:

some caution needs to be exercised before characterising words in a complex composite registered trade mark as an ‘essential feature’ of that mark in assessing the question of deceptive similarity. If such a characterisation is made too readily, it effectively converts a composite mark into something quite different.

However, as the Full Federal Court noted in the same case at [100], ‘everything depends on the particular circumstances of the case’. The correct approach, as noted above, is for decision makers to proceed on the basis that descriptive words may to some extent be discounted, but must not be ignored entirely.

Crazy Ron’s compared against CRAZY RON/CRAZY RON’S and held that CRAZY JOHN was not an essential feature of the stylised trade mark. The trade marks were then not considered deceptively similar.

The following examples provide illustrations of comparisons between compound marks featuring non-distinctive word components, showing the range of factors that have been taken into account in determining whether the marks in question were or were not deceptively similar.

Examples

Example 1

Mount Everest Mineral Water Ltd [2012] ATMO 65

Marks being compared:

Decision: Sufficiently Different

Reasons/Quote: Reasons for this decision include:

In my consideration, confusion between the Trade Mark and those cited against it might only arise if it is likely, on the balance of probabilities, that consumers of the goods will view the words HIMALAYAN…MINERAL WATER or HIMALAYAN SPRING MINERAL WATER as acting as a badge of trade origin as opposed to geographical origin of the spring water (at [28).

Example 2

The BBQ Store Pty Ltd v BBQ Factory Pty Ltd [2019] ATMO 132

Marks Being Compared:

Decision: Deceptively Similar

Reasons/Quote: Reasons for this decision include:

The flame is probably the single most memorable element of the [applicant’s] Trade Mark, yet even it is somewhat descriptive of the Goods … there is very little likelihood that the relevant consumer would recall in any detail the look of the flame. The rest of the device is a quite unremarkable black background … ‘The BBQ store’, as the phrase appears in the Trade Mark, is very descriptive of the Goods … the concept of this type of outdoor cooking implement is all that is likely to be remembered … The general impression likely to be taken away by the relevant consumer would in my estimation be of barbecue seller that uses a flame in its logo” (at [26])

“The Opponent’s Mark also includes a descriptive device—a skewer loaded with what appears to be an orange slab of meat, being licked by red flames from beneath. This device is visually distinct from the flame in the [applicant’s] Trade Marks, but conceptually they share a motif of fire. The words ‘TheBBQ Store’, are slightly differently arranged in the Opponent’s Mark. But through the lens of imperfect recollection they are visually, aurally and conceptually indistinguishable from the Trade Mark—the relevant consumer cannot be expected to note, let alone recall, that the Opponent uses a superscript ‘The’ and the Applicant a lowercase ‘store’. Even with the necessary discounts applied to this descriptive phrase, that both marks use the exact same descriptive words in precisely the same order can only add to their visual and conceptual similarity (at [27])

Example 3

Cars on Demand IP Pty Ltd v Cars on Demand Ltd [2014] ATMO 87

Marks being compared:

Decision: Sufficiently Different

Reasons/Quote: Reasons for this decision include:

I am satisfied on the evidence not only that traders in relevant Class 39 services are likely to want to use the words “cars on demand”, or “on demand”, in connection with car hire for the sake of their ordinary significance and without improper motive, but that several have already done so” (at [36])

“Since the Opposed Mark is otherwise quite different from, and readily distinguishable from, the Opponent’s Device Mark when the marks are compared as wholes, my finding, in summary, is that the Opposed Mark is not deceptively similar to the Opponent’s Device Mark (at [37])

Example 4

Combined Communications Pty Ltd v Combined Communication Solutions Pty Ltd [2014] ATMO 117

Marks being compared:

Decision: Sufficiently Different (composite logo), Deceptively Similar (plain words)

Reasons/Quote:

Reasons for this decision include:

in any comparison of the trade marks in question, the expressions ‘Combined Communications’ and ‘Combined Communication Solutions’ should be subject to very heavy discounting (at [65])

In the Opposed Word Trade Mark there is no accompanying device to aid potential purchasers in distinguishing between it and the Opponent’s Registered Trade Mark. Deception or confusion is therefore likely to arise out of the use of the Opposed Word Trade Mark (at [77])

I therefore find that the Opposed Word Trade Mark is deceptively similar to the Opponent’s Registered Trade Mark but that the Opposed Logo Trade Mark is not deceptively similar to the Opponent’s Registered Trade Mark (at [78])

Example 5

REA Group Ltd v Real Estate 1 Ltd [2013] FCA 559; (2013) 217 FCR 327

Marks being compared:

Decision: Sufficiently different

Reasons/Quote: Reasons for this decision include:

The realestate.com.au logo has arguably three components… No component on its own is an essential feature…the placement of the device in the middle of the [realEstate1] logo is a strongly distinguishing feature. That placement has the effect of sidelining “.com.au” and projecting “realEstate1’ as the dominant element (at [232]).

Decision: Deceptively similar

Reasons/Quote:

[This is] a situation where the highly descriptive nature of the second-level domain (“realestate”) makes a suffix such as “.com.au” essential to brand or name recognition…A real danger of confusion again arises because in the scanning process which may occur on a results page, some consumers will miss the indistinctive “I” (at [245]).

Decision: Deceptively similar

Reasons/Quote:

[T]he essential feature of REA’s realcommercial.com.au trade mark [are the] words “realcommercial”…The same concocted words are prominent in Real Estate 1’s logo where they appear as the strongest element of the logo. Whilst there are differences in font, colour and the use and placement of the house device as well as the existence of additional features, those elements do not do enough…to avoid the real danger of deception or confusion created by the common essential feature (at [236]).

6.9 Type of customer

As was pointed out in Crook's Trade Mark, (1914) 31 RPC 79 at 85, a trade mark should not be barred from registration because “unusually stupid people, fools or idiots would be deceived”. A similar observation was made in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v F. S. Walton & Co Ltd, [1937] HCA 51 at 658, where Dixon and McTiernan JJ said

The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard.

6.10 Type of goods and services

The nature of the goods and the market through which they will be purchased will affect the care with which purchasers will view trade marks on goods which they select. Generally the more expensive the items being considered the less likely the purchaser is to be deceived or confused by similarities between the trade marks under which they are sold. Similarly, highly technical goods would probably be purchased only by persons who would not be deceived by somewhat similar trade marks. On the other hand, goods such as soaps would be purchased by a large number of people who might well be deceived by seeing goods bearing a similar trade mark.

The same principles would apply to services. A similar trade mark used in respect of shoe repair services provided by different enterprises is more likely to be a source of confusion than if the services were specialist medical services.

Some pharmaceutical lines are available only on prescription, or are covered by other regulations such as Health or Food and Drugs Acts. In such cases the principles considered in Bayer’s Application (1947) 64 RPC 125, may be applicable. In that case the marks under comparison were "Diasil" in respect of 'sulphadiazine' a pharmaceutical preparation available only on prescription, and "Alasil" in respect of 'chemical substances prepared for use in medicine and pharmacy'. The fact that the goods covered by the mark "Diasil" were only available on a doctor's prescription was an important consideration in reaching the conclusion that the marks could co-exist on the Register.

For further guidance in the consideration of this aspect of comparison, see:

Vagisil where the context of the claimed goods and services was considered to determine the descriptive value of the shared VAG/VAGI element between VAGISIL and VAGISAN.

and

Jafferjee in which the use of trade marks stamped on flour sacks was considered to increase the likelihood of confusion.

6.11 Trade marks in a language other than English

The usual tests for comparing word trade marks are applied when deciding whether words rendered in a non-English language are deceptively similar to trade marks already on the Register. This applies whether the trade marks being compared are both rendered in Roman characters or in the letters or characters of any other system of writing, such as Chinese or Arabic. The visual, aural, and conceptual impressions of the respective trade marks must be considered in the context of the market for the goods or services.

It must be kept in mind that Australia is a multicultural society and many languages are spoken or understood by Australian consumers. An assessment in each case should be made of the likelihood that the ordinary purchasers of the goods or services will understand the meaning and pronounciation of the non-English words constituting the trade mark. This will vary with the nature of the particular goods or services and trade marks as indicated by the following situations:

Visual and aural features of a foreign word will generally contribute more to the impression of a trade mark where the target audience are generally not speakers of the foreign language in question. In such cases, similarities in meaning between two marks is a less persuasive factor.

Similar meanings of respective trade marks under comparison may be a more persuasive factor where the target audience for the goods or services could include a significant number of speakers of a particular language. For example, the presence of an English language word and a foreign language word as the essential features of two trade marks both covering migration services, where the respective words have an identical or very similar meaning, may lead to confusion if the target audience includes many speakers of the relevant foreign language.

If the goods or services are very specialised and/or, expensive, considerable care would be exercised in their selection and purchase. In such circumstances even minor difference between trade marks might serve to differentiate the goods or services.

When comparing non-Roman characters and their transliteration (i.e. their Romanised phonetic equivalent), where both would be seen as reference to the same words, it may lead to deception or confusion. The reasons for this are that transliterations are usually phonetically similar, if not identical, to the original characters, and the meaning or impression of each would be the same to speakers of that language.

When the comparison is between a non-English language trade mark and an English language trade mark, the same principles apply. In general, except where the words are visually or aurally similar, the English translation of a non-English language trade mark will not be cited as the basis for rejecting an application under s 44. For example, RED MAN will not be cited against the French words ROUGE HOMME or the Chinese or Arabic characters meaning “red man”.

6.12 Words and devices depicting words

A word and an equivalent pictorial representation may be found to be deceptively similar, based upon the fact that a person of normal intelligence and memory would retain and carry away the same overall impression. The examiner needs to consider the name and idea that would be associated with the particular device trade mark compared to the name and idea conveyed by the word trade mark. A ground for rejection under s 44 will exist if when comparing the trade marks in question, the conclusion is that the name and idea conveyed are exactly the same.

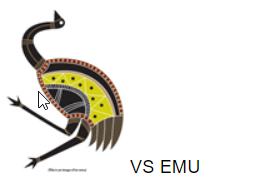

In Constellation Australia Limited v Littore Family Wines Pty Ltd [2011] ATMO 47, when finding the following trade marks to be deceptively similar:

the Hearing Officer, in referencing Jafferjee, stated at 30:

The principle in [Jafferjee v. Scarlett] came down to the ‘idea of the mark’. Whatever may be said of the competing ideas evident in the devices in Jafferjee, the only possible conclusion in the present opposition is that the idea of the applicant’s EMU device is “EMU”, precisely the same idea and name that would be associated with the opponent’s trade mark for the word EMU.

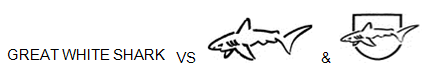

A contrary outcome can be seen in Wolter Joose on behalf of Joose Apparel Pty Ltd v Great White Shark Enterprises Inc [1999] ATMO 59 where the following trade marks were found NOT to be deceptively similar:

In that decision, the Hearing Officer states that whilst the ‘devices are definitely depictions of sharks…there is nothing to say that they are Great White Sharks’.

Amended Reasons

| Amended Reason | Date Amended |

|---|---|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

Images republished. |

|

Added images to display externally |

|

6.4 Trade marks that share the same or similar element - content updated to table format |

|

6.4 Marks which contain another trade mark renamed to 6.4 Trade marks that share the same or similar element and content updated. |

|

Content updated. |

|

Reputation content updated |

|

Update hyperlinks |

|

reorder of content |

|

New content at Part 26.6.7 and reorder of numbering on page |

|

Minor formatting change |