- Home

- 2. About this Manual

- 2.1 Purpose of the Manual

- 2.2 Navigating the Manual

- 2.3 Determining Changes to the Manual

- 2.4 Governance for Editing the Manual

- 2.5 Periodic Review and Maintenance

- 3. Quality and Customer Engagement

- 3.1 Quality

- 3.2 Customer Service Charter (Timeliness Guidelines)

- 3.3 Efficient Examination

- 3.3.1 Use of FERs (Earlier Search and Examination Reports)

- 3.3.2 General Approach to Examination

- 3.3.3 Reserving Opinion and Restricting the Search

- 3.3.4 Communicating with the Applicant and Third Parties

- 3.4 Assisting Unrepresented Applicants

- 3.5 Staff Delegations, and Restrictions on Providing Customer Assistance

- 4. Classification and Searching

- 4.1 Search Theory

- 4.2 Patent Classifications

- 4.2.1 Patent Classification Systems

- 4.2.1.1 International Patent Classification (IPC)

- 4.2.1.1.1 Structure of the IPC

- 4.2.1.1.2 Headings and Titles

- 4.2.1.1.3 Definitions, Warnings and Notes

- 4.2.1.1.4 Function-Oriented and Application-Oriented Places

- 4.2.1.1.5 References

- 4.2.1.1.6 Indexing Codes

- 4.2.1.2 Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC)

- 4.2.2 Principles of Classification

- 4.2.2.1 Invention Information and Additional Information

- 4.2.2.1.1 Application of Indexing Codes/2000 Series

- 4.2.2.1.2 Classifying in Residual Places

- 4.2.2.1.3 Places that cannot be the First Symbol

- 4.2.2.2 Classification Priority Rules

- 4.2.2.2.1 Common Rule

- 4.2.2.2.2 First Place Priority Rule

- 4.2.2.2.3 Last Place Priority Rule

- 4.2.2.2.4 Special Rules

- 4.2.2.2.5 Classifying a Combination of Technical Subjects

- 4.2.2.3 Classifying in Function-Oriented and Application-Oriented Places

- 4.2.2.4 Classifying Chemical Compounds

- 4.2.2.5 CPC Classification Rules

- 4.2.2.6 Classification using C-sets

- 4.2.3 Other Classification Information

- 4.2.3.1 Sub-Codes - Discontinued

- 4.2.3.2 The Australian Classification System - Discontinued

- 4.2.3.3 Indexing According to IPC Edition (2006) - Discontinued

- 4.2.3.4 Master Classification Database (MDC)

- 4.2.3.5 Recording Classification Symbols on Machine-Readable Records

- 4.2.3.6 Presentation of Classification Symbols and Indexing Codes on Patent Documents

- 4.3 Initial Search Considerations

- 4.3.1 Construction and the Inventive Concept

- 4.3.2 Earlier Search Results

- 4.3.3 Additional Searching

- 4.3.4 Top-Up Searching

- 4.3.5 Preliminary Search

- 4.3.6 Applicant and/or Inventor Name Searching

- 4.4 Development of the Search Strategy

- 4.4.1 Three Person Team (3PT)

- 4.4.2 Search Strategy Considerations

- 4.4.2.1 Independent Claims

- 4.4.2.2 Dependent Claims

- 4.4.2.3 Broad Claims

- 4.4.2.4 Reserving the Search

- 4.4.2.5 Controlled Language

- 4.4.3 Search Area

- 4.5 Conducting the Search

- 4.6 Recording the Search Details

- 4.7 Annexures

- Annex D - Search Information Statement

- Annex E - Examples and Instructions for completing the SIS for Sequence and Chemical Structure Searches

- Annex F - When to Complete the Search Information Statement (SIS)

- Annex N - Guidelines for Searching Indian TKDL

- Annex P - The Role of the Three Person Team (3PT) in Searching

- 4.8 User Guides

- 5. National

- 5.1 Procedures

- 5.2 Understanding Legislation

- 5.2.1 Modern Australian Law

- 5.2.2 Working with case law

- 5.2.3 Working with statute

- 5.2.4 Practical guide to interpreting legislation

- 5.3 Formalities and Forms

- 5.3.1 Formalities Checking

- 5.3.1.1 Formalities Required and Assessed at Filing

- 5.3.1.2 Credible Address for Service

- 5.3.1.3 Formalities Required and Assessed During Examination

- 5.3.2 Formal requirements of the Specification

- 5.3.2.1 Title of the Application

- 5.3.2.2 Abstracts

- 5.3.2.3 Requirements for Text, Pagination, Formulas, Equations, Drawings, Graphics, and Photographs

- 5.3.2.4 Substitute Pages to comply with formalities

- 5.3.2.5 Requirements for Amino Acid and Nucleotide Sequences

- 5.3.2.6 Scandalous Matter

- 5.3.3 Approved Forms (including patent request)

- 5.3.4 Signature Requirements for Forms and Other Documents

- 5.3.5 Return or Deletion of Documents

- 5.4 Entitlement

- 5.4.1 Who can file and who can be granted a patent

- 5.4.2 Statement of entitlement

- 5.4.3 Artificial Intelligence - Inventorship and Entitlement

- 5.4.4 Annex A - Examples of Legal Persons

- 5.4.5 Annex B - Examples of Organisations of Uncertain Status as Legal Persons

- 5.5 Construction of Specifications, Claims, and Claim Types

- 5.5.1 Purpose of Construction

- 5.5.2 Considerations Relevant to Construction of the Specification

- 5.5.2.1 Initial Considerations

- 5.5.2.2 The Addressee

- 5.5.2.3 The Role of Common General Knowledge

- 5.5.2.4 The Invention Described

- 5.5.3 Rules of Construction for a Specification

- 5.5.3.1 Words are Given Plain Meaning

- 5.5.3.2 Specification Read as a Whole

- 5.5.3.3 Purposive Construction

- 5.5.3.4 Dictionary Principle

- 5.5.3.5 Reject the Absurd

- 5.5.3.6 Description Construed as a Technical Document

- 5.5.3.7 Errors, Mistakes, Omissions

- 5.5.4 Claim Construction and Claim Types

- 5.5.4.1 Claims are Construed as a Legal Document

- 5.5.4.2 Presumption Against Redundancy

- 5.5.4.3 Omnibus Claims

- 5.5.4.4 Swiss Claims

- 5.5.4.5 Product by Process Claims

- 5.5.4.6 Parametric Claims

- 5.5.4.7 ‘For Use’, ‘When Used’ and Similar Wording in Claims

- 5.5.4.8 ‘Comprises‘, ‘Includes‘, ‘Consists of‘ and ‘Contains‘ and Similar Wording in Claims

- 5.5.4.9 Reference Numerals in Claims

- 5.5.4.10 Relative Terms

- 5.5.4.11 ‘Substantially‘, ‘About‘, ‘Generally’

- 5.5.4.12 Appended Claims

- 5.6 Examination

- 5.6.1 Relevant Dates, Definitions, Legal Standards and Other Prescribed Matters (e.g Publication)

- 5.6.1.1 Priority dates and Filing Dates

- 5.6.1.2 Effect of Publication

- 5.6.1.3 Definitions (Invention, Alleged Invention, Meaning of a Document etc.)

- 5.6.1.4 Balance of Probabilities Standard

- 5.6.1.5 Application of the Balance of Probabilities in Examination

- 5.6.2 Factors to consider before commencing examination

- 5.6.2.1 Request for Examination

- 5.6.2.2 Application in a State of Lapse?

- 5.6.2.3 Extension of Time Requested (s223 actions)

- 5.6.2.4 Payment of Fees

- 5.6.2.5 Translations of Specifications, Article 19 and Article 34 Amendments (Requirements for Certification, Poor Translations)

- 5.6.2.6 Obtaining Priority Documents

- 5.6.2.7 Excess Claims Fees and Invitation to Pay

- 5.6.2.8 Report Dispatch, Correction of Report etc.

- 5.6.2.9 Further Report Considerations

- 5.6.2.10 Convention applications

- 5.6.3 The Specification and Claims to Examine

- 5.6.3.1 Consideration of Amendments Made prior to examination

- 5.6.3.2 Claims are directed to a Single Invention (Unity)

- 5.6.3.3 Omnibus claims – References to the Descriptions or Drawings

- 5.6.3.4 Provisional specifications - Examination

- 5.6.4 Citations: Prior Art Base and Construction of Prior Art

- 5.6.4.1 Prior Art - What is Included (Definition From the Act, Publicly Available, Exclusions, Grace Period)

- 5.6.4.2 Construing a Citation

- 5.6.4.3 Level of Disclosure Required (Enabling Disclosure, Clear and Unmistakable Directions etc)

- 5.6.4.4 Single Source of Information, Combination of Documents

- 5.6.4.5 Third Party Notifications

- 5.6.4.6 Identifying and Raising Citations

- 5.6.5 Novelty, Whole of Contents, Grace Periods, Secret Use

- 5.6.5.1 Determining Novelty

- 5.6.5.2 Whole of Contents

- 5.6.5.3 Prior Use, Secret Use and Confidential Information

- 5.6.5.4 Novelty - Specific Examples

- 5.6.5.5 Selections

- 5.6.5.6 Issues Specific to Chemical Compositions

- 5.6.6 Inventive Step

- 5.6.6.1 Inventive Step Requirements

- 5.6.6.2 Information for Assessing Inventive Step

- 5.6.6.3 Tests for Inventive Step

- 5.6.6.4 Assessing Inventive Step

- 5.6.6.5 Indicators of Inventive Step

- 5.6.6.6 Issues Specific to Chemical Compositions

- 5.6.7 Full Disclosure, Sufficiency, Clarity and Support (S40 considerations)

- 5.6.7.1 Claims are Clear and Succinct

- 5.6.7.2 Clear and Complete Disclosure s40(2)(a)

- 5.6.7.3 Support for the Claims s40(3)

- 5.6.7.4 Difference Between ‘Clear and Complete Disclosure’ and ‘Support’

- 5.6.7.5 Best Method

- 5.6.7.6 Complete Disclosure Micro-Organisms and Other Life Forms (Budapest Treaty, Deposit Requirements)

- 5.6.7.7 Claims define the Invention

- 5.6.7.8 Annex A - Examples: Subsections 40(2)(a) and 40(3)

- 5.6.8 Patent Eligible Subject Matter (Manner of Manufacture, Usefulness)

- 5.6.8.1 General Principles-Assessing Manner of Manufacture

- 5.6.8.2 Alleged Invention

- 5.6.8.3 Fine Arts

- 5.6.8.4 Discoveries, Ideas, Scientific Theories, Schemes and Plans

- 5.6.8.5 Printed Matter

- 5.6.8.6 Computer Implemented Inventions, Schemes and Business Methods

- 5.6.8.7 Games and Gaming Machines

- 5.6.8.8 Mathematical Algorithms

- 5.6.8.9 Methods of Testing, Observation and Measurement

- 5.6.8.10 Mere Working Directions

- 5.6.8.11 Nucleic Acids and Genetic Information

- 5.6.8.12 Micro-Organisms and Other Life Forms

- 5.6.8.13 Treatment of Human Beings

- 5.6.8.14 Human Beings and Biological Processes for Their Generation

- 5.6.8.15 Agriculture and Horticulture

- 5.6.8.16 Combinations, Collocations, Kits, Packages and Mere Admixtures

- 5.6.8.17 New Uses

- 5.6.8.18 Other Issues e.g. Contrary to Law, Mere Admixtures

- 5.6.8.19 Useful (Utility)

- 5.6.8.20 Annex A - History of Manner of Manufacture

- 5.6.9 Acceptance, Grant and Refusal of Applications

- 5.6.9.1 Conditions and Time for Acceptance

- 5.6.9.2 Postponement of Acceptance

- 5.6.9.3 Extension of Acceptance Period

- 5.6.9.4 Revocation of Acceptance

- 5.6.9.5 Refusal of Acceptance-Specific Circumstances

- 5.6.9.6 Refusal of an Application

- 5.6.9.7 Continued Examination-Result of a Decision

- 5.6.9.8 Lapsing of an Application

- 5.6.9.9 Withdrawal of an Application

- 5.6.9.10 Double Patenting - S64(2) and 101B(2)(h) - Multiple Applications

- 5.6.9.11 Parallel applications (applications for both innovation and standard)

- 5.6.9.12 Register of Patents

- 5.6.9.13 Annex A - Example Bar-to-Grant Letter (Accepted Despite Multiple Inventions)

- 5.6.9.14 Acceptance and QRS Issues

- 5.6.10 Divisional Applications

- 5.6.10.1 Requirements to Claim Divisional Status

- 5.6.10.2 Priority Entitlement

- 5.6.10.3 Time Limits for Filing

- 5.6.10.4 Status of the Parent

- 5.6.10.5 Examination of Divisional Applications

- 5.6.10.6 Innovation Divisional Applications

- 5.6.10.7 Annex A - Procedural Outline to Divisional Examination

- 5.6.11 Patents of Addition

- 5.6.11.1 Conditions for Filing

- 5.6.11.2 Improvement or Modification

- 5.6.11.3 Differentiation from the Parent

- 5.6.11.4 Examination of Additional Applications

- 5.6.11.5 Amendment of the Parent

- 5.6.11.6 Annex A - Procedural Outline to Patents of Addition Examination

- 5.6.12 Preliminary search and Opinion (PSO)

- 5.6.12.1 Requests for PSO

- 5.6.12.2 PSO - Search and Examination Procedure

- 5.6.12.3 PSO - Report Requirements

- 5.6.12.4 Response to the PSO

- 5.6.13 Re-Examination

- 5.6.13.1 Commencing Re-Examination

- 5.6.13.2 Re-Examination Process

- 5.6.13.3 Completion of Re-Examination

- 5.6.13.4 Refusal to Grant or Revocation Following Re-Examination

- 5.6.14 Prohibition Orders- Applications Concerning Defence of the Commonwealth and/or involving Associated Technology (e.g. enrichment of nuclear material)

- 5.6.14.1 Effect of Prohibition orders

- 5.6.14.2 Applications Concerning Defence of the Commonwealth

- 5.6.14.3 Applications Concerning ‘Associated Technology’ (Chapter 15 Applications)

- 5.6.15 Innovation Patents

- 5.6.15.1 The Innovation Patent System

- 5.6.15.2 Types of Innovation Patents

- 5.6.15.3 Formalities Check for Innovation Patents

- 5.6.15.4 Examination of Innovation Patents

- 5.6.15.5 Determining Innovative step

- 5.6.15.6 Certification, Opposition, Ceasing/Expiring of Innovation Patents

- 5.6.15.7 Annex - Innovation Patent Certification Form

- 5.6.16 Annex A - Procedural Outline for Full Examination of a Standard Patent Application

- 5.6.17 Annex B - Examination of National Phase Applications: Indicators of Special or Different Considerations

- 5.6.18 Annex C - Applicant and Inventor Details as Shown on PCT Pamphlet Front Page

- 5.6.19 Annex D - Example of PCT Pamphlet Front Page

- 5.7 Amendments

- 5.7.1 What can be Amended and When

- 5.7.1.1 What Documents can be Amended?

- 5.7.1.2 Who can Request Amendments (incl consent of licensees/mortgagees)?

- 5.7.1.3 When can Amendments be Requested?

- 5.7.1.4 Requirements to provide Reasons for Amendments

- 5.7.1.5 Withdrawal of Amendments

- 5.7.1.6 Circumstances where an amendment cannot be processed (i.e. pending court proceedings, Application has been Refused)

- 5.7.1.7 Granting Leave to Amend

- 5.7.1.8 Fees Associated with Amendments

- 5.7.1.9 Annex A - Guidelines for Completing the Voluntary Section 104 Allowance Form

- 5.7.2 Amendment of the Patent Request and Other Filed Documents

- 5.7.2.1 Form of the Request to Amend the Patent Request

- 5.7.2.2 Non-Allowable Amendments to Patent Request

- 5.7.2.3 Changing the Applicant or Nominated Person

- 5.7.2.4 Converting the Application

- 5.7.2.5 Amendments to the Notice of Entitlement and Other Documents

- 5.7.3 Amendments-Provisional Applications

- 5.7.4 Amendments to Complete Specifications

- 5.7.4.1 Form of proposed amendments (statement of proposed amendments)

- 5.7.4.2 Allowability of Amendments Prior to Acceptance

- 5.7.4.3 Allowability of Amendments After Acceptance

- 5.7.4.4 Allowability of Amendments After Grant

- 5.7.4.5 Amendments not Otherwise Allowable

- 5.7.4.6 Opposition to Amendments

- 5.7.4.7 Annex A - Amended Claims Format

- 5.7.5 Amendments to Correct a Clerical Error or Obvious Mistake

- 5.7.5.1 Definition of Clerical Error

- 5.7.5.2 Definition of Obvious Mistake

- 5.7.5.3 Evidence required to prove a Clerical Error or Obvious Mistake

- 5.7.6 Amendments Relating to Micro-Organisms and Sequence Listings

- 5.7.6.1 Insertion or Alteration of Sec 6(c) Information

- 5.7.6.2 Amendments or Corrections of Sequence Listings

- 5.7.7 Amendments during Opposition Proceedings

- 5.7.7.1 Initial Processing of the Request to Amend During Oppositions

- 5.7.7.2 Considering the Amendments and Comments from the Opponent

- 5.7.7.3 Considering Amendments as a Result of a Hearing Decision

- 5.7.7.4 Amendments where Decision of the Commissioner is Appealed

- 5.7.7.5 Annex A - Section 104 Amendments During Opposition Proceedings: Check Sheet

- 6. International

- 6.1 International Searching

- 6.1.1 Procedural Outline - PCT International Search

- 6.1.2 Introduction- International Searching

- 6.1.2.1 Overview- International Searching

- 6.1.2.2 Overview-International Search Opinion (ISO)

- 6.1.2.3 General Procedures

- 6.1.2.4 Extent of Search

- 6.1.2.5 Minimum Documentation

- 6.1.2.6 Examination Section Procedures

- 6.1.2.7 Searching Examiner

- 6.1.2.8 Other Considerations

- 6.1.2.9 Copending Applications

- 6.1.3 Search Allocation and Preliminary Classification

- 6.1.4 Unity of Invention

- 6.1.4.1 Unity of Invention Background

- 6.1.4.2 Determining Lack of Unity

- 6.1.4.3 Combinations of Different Categories of Claims

- 6.1.4.4 Markush Practice

- 6.1.4.5 Intermediate and Final Products in Chemical Applications

- 6.1.4.6 Biotechnological Inventions

- 6.1.4.7 Single General Inventive Concept

- 6.1.4.8 A Priori and A Posteriori Lack of Unity

- 6.1.4.9 Issuing the Invitation to Pay Additional Search Fees

- 6.1.4.10 Unsupported, Unclear, Long and/or Complex Claim Sets with Clear Lack of Unity

- 6.1.4.11 Payment of Additional Search Fees Under Protest

- 6.1.4.12 Completing the Search Report

- 6.1.4.13 Time for Completing the Search Report

- 6.1.4.14 Reported Decisions

- 6.1.4.15 Other Decisions from the EPO

- 6.1.5 Abstract and Title

- 6.1.6 Subjects to be Excluded from the Search

- 6.1.7 Claim Interpretation, Broad Claims, PCT Articles 5 and 6

- 6.1.7.1 Claim Interpretation According to the PCT Guidelines

- 6.1.7.1.1 PCT Guideline References and Flow Chart

- 6.1.7.1.2 Overview of the Hierarchy

- 6.1.7.1.3 Special Meaning, Ordinary Meaning, Everyday Meaning

- 6.1.7.1.4 Closed and Open Definitions and Implications for Interpretation

- 6.1.7.1.5 Implications of the Hierarchy on Searching

- 6.1.7.1.6 Practices for the Interpretation of Claims

- 6.1.7.1.7 Interpretation of Citations - Inherency

- 6.1.7.2 Broad Claims

- 6.1.7.3 PCT Articles 5 and 6

- 6.1.7.4 Claims Lacking Clarity and Excessive/Multitudinous Claims

- 6.1.7.5 Procedure for Informal Communication with the Applicant

- 6.1.8 Search Strategy

- 6.1.8.1 Introduction

- 6.1.8.2 The Three Person Team (3PT)

- 6.1.8.3 Area of Search

- 6.1.8.4 Search Considerations

- 6.1.9 Basis of the Search

- 6.1.10 Non-Patent Literature

- 6.1.11 Search Procedure

- 6.1.11.1 Overview - Novelty / Inventive Step

- 6.1.11.2 Inventive Step

- 6.1.11.3 Searching Product by Process Claims

- 6.1.11.4 Dates Searched

- 6.1.11.5 Conducting the Search

- 6.1.11.6 Useful Techniques ("piggy back/forward" searching)

- 6.1.11.7 Obtaining Full Copies

- 6.1.11.8 Considering and Culling the Documents

- 6.1.11.9 Ending the Search

- 6.1.11.10 Categorising the Citations

- 6.1.11.11 Grouping the Claims

- 6.1.12 Search Report and Notification Form Completion

- 6.1.12.1 Background Search Report and Notification Form Completion

- 6.1.12.2 Applicant Details

- 6.1.12.3 General Details

- 6.1.12.4 Fields Searched

- 6.1.12.5 Documents Considered to be Relevant

- 6.1.12.5.1 Selection of Documents Considered to be Relevant

- 6.1.12.5.2 Citation Category

- 6.1.12.5.3 Citation of Prior Art Documents

- 6.1.12.5.4 Citation of URLs

- 6.1.12.5.5 Citation Examples

- 6.1.12.5.6 Citing Patent Documents Retrieved from EPOQUE

- 6.1.12.5.7 Relevant Claim Numbers

- 6.1.12.6 Family Member Identification

- 6.1.12.7 Date of Actual Completion of the Search

- 6.1.12.8 Refund Due

- 6.1.12.9 Contents of Case File at Completion

- 6.1.13 Reissued, Amended or Corrected ISRs and ISOs

- 6.1.14 Priority Document

- 6.1.15 Foreign Patent Search Aids and Documentation

- 6.1.16 Assistance with Foreign Languages

- 6.1.17 Rule 91 Obvious Mistakes in Documents

- 6.1.18 Nucleotide and/or Amino Acid Sequence Listings

- 6.1.18.1 Background Nucleotide and/or Amino Acid Sequence Listings

- 6.1.18.2 Office Practice

- 6.1.18.3 Summary

- 6.1.19 Annexes

- Annex A - Blank ISR

- Annex B - Completed ISR

- Annex C - Completed ISR

- Annex D - Declaration of Non-Establishment of ISR

- Annex E - Completed Invitation to pay additional fees

- Annex F - Completed ISR with unity observations

- Annex H - Searching Broad Claims

- Annex I - Completed notification of change of abstract

- Annex J - Completed notification of decision concerning request for rectification

- Annex K - The role of the 3 Person Team in Searching

- Annex S - Refund of Search Fees

- Annex U - ISR Quality Checklist

- Annex V - Internet Searching

- Annex W - Obtaining full text from internet

- Annex Z - USPTO kind codes

- Annex AA - Markush Claims

- Annex BB - Article 5/6 Comparisons

- 6.2 International Type Searching

- 6.2.1 Procedural Outline International Type Search Report

- 6.2.2 Introduction - International Type Searching

- 6.2.3 Classification and Search Indication

- 6.2.4 Unity of Invention

- 6.2.5 Subjects to be Excluded from the Search

- 6.2.6 Obscurities, Inconsistencies or Contradictions

- 6.2.7 Abstract and Title

- 6.2.8 Search Report

- 6.2.9 Completing Search Report and Opinion Form

- 6.2.10 Annexes

- 6.3 International Examination

- 6.3.1 Procedural Outline Written Opinion

- 6.3.2 Introduction International Examination

- 6.3.3 The Demand and IPRPII

- 6.3.4 Top-up Search

- 6.3.5 First IPE action

- 6.3.5.1 Introduction - First IPE Action

- 6.3.5.2 Supplementary International Search Report

- 6.3.5.3 PCT Third Party Observations

- 6.3.6 Response to Opinion

- 6.3.7 IPRPII and Notification

- 6.3.8 Completing ISO, IPEO and IPRPII Forms

- 6.3.8.1 Front Page and Notification Application Details

- 6.3.8.2 Box I Basis of Opinion/Report for ISOs, IPEOs and IPRPs

- 6.3.8.3 Box II Priority

- 6.3.8.4 Box III Non-establishment of Opinion

- 6.3.8.5 Box IV Unity of Invention

- 6.3.8.6 Box V Reasoned Statement Regarding Novelty, Inventive Step & Industrial Applicability

- 6.3.8.7 Box VI Certain Documents Cited

- 6.3.8.8 Box VII Certain Defects

- 6.3.8.9 Box VIII Certain Observations

- 6.3.9 General Considerations

- 6.3.9.1 Article 19 or Article 34(2)(b) Amendments

- 6.3.9.2 Formalities

- 6.3.9.3 General Notes on Form Completion

- 6.3.9.4 Rule 91 Obvious Mistakes in Documents

- 6.3.9.5 Processing withdrawals of PCTs

- 6.3.10 Annexes

- Annex A - Written Opinion-ISA

- Annex B - Written Opinion-IPEO

- Annex C - Notification of Transmittal of IPERII

- Annex D - IPRPII

- Annex E - IPRPII Clear Novel and Inventive Box V Only

- Annex F - Invitation to Restrict/Pay Additional Fees - Unity

- Annex G - Extension of Time Limit

- Annex H - IPE Quality Checklist

- Annex I - Examples of Inventive Step Objections

- Annex J - Examples of Objections under PCT Articles 5 and 6

- Annex K - Example of PCT Third Party Observations

- Annex L - Blank Written Opinion - ISA

- Annex M - Blank Written Opinion - IPEO

- Annex N - Blank IPRPII

- Annex O - ISO/ISR with Omnibus Claims

- Annex P - PCT Timeline

- Annex Z - Best Practice Examples

- 6.4 Fiji Applications

- 6.4.1 Introduction

- 6.4.2 Completion Time and Priority

- 6.4.3 Initial Processing

- 6.4.4 Search Procedure

- 6.4.5 Search Report and Advisory Opinion

- 6.4.6 Further Advisory Opinion

- 6.4.7 Final Processing

- 6.4.8 Annexes

- 6.5 Thai Applications

- 6.5.1 Introduction to Thai Applications

- 6.5.2 Completion Time and Priority

- 6.5.3 Initial Processing

- 6.5.4 Search Procedure

- 6.5.5 Search Report

- 6.5.6 Final Processing

- 6.5.7 Annex A - Thai Search Report

- 6.6 WIPO Searches

- 6.6.1 Introduction

- 6.6.2 Completion Time and Priority

- 6.6.3 Initial Processing

- 6.6.4 Search Procedure

- 6.6.5 Search Report

- 6.6.6 Final Processing

- 6.6.7 Annexes

- 6.7 Other Countries

- 6.8 PCT Articles, Regulations and Guidelines et al

- 6.9 Miscellaneous

- 7. Oppositions, Disputes and Extensions

- 7.1 Role and Powers of the Commissioner in Hearings

- 7.2 Oppositions, Disputes and other proceedings-Procedural summaries

- 7.2.1 Oppositions to grant of a standard patent-Section 59 oppositions

- 7.2.1.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing a Notice of Opposition

- 7.2.1.2 Filing the Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.2.1.3 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.1.4 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.2 Opposition to Innovation Patents-Section 101M Oppositions

- 7.2.2.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing the Opposition Documents

- 7.2.2.2 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.2.3 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.3 Oppositions to an Extension of Term of a Pharmaceutical Patent (Section 75(1) Oppositions)

- 7.2.3.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing a Notice of Opposition

- 7.2.3.2 Filing the Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.2.3.3 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.3.4 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.4 Oppositions to Request to Amend an Application or Other Filed Document (Section 104(4) Oppositions)

- 7.2.4.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing a Notice of Opposition

- 7.2.4.2 Filing the Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.2.4.3 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.4.4 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.5 Oppositions to Extensions of Time Under Section 223 (Section 223(6) Oppositions

- 7.2.5.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing a Notice of Opposition

- 7.2.5.2 Filing the Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.2.5.3 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.5.4 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.6 Oppositions to Grant of a Licence (Regulation 22.21(4) Oppositions)

- 7.2.6.1 Commencing the Opposition - Filing a Notice of Opposition

- 7.2.6.2 Filing the Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.2.6.3 Evidence and Evidentiary Periods

- 7.2.6.4 Finalising the Opposition

- 7.2.7 Disputes Between Applicants and Co-Owners (Directions Under Section17 and Determinations Under Section 32)

- 7.2.8 Entitlement Disputes (Applications Under Sections 33-36 and 191A)

- 7.3 Directions

- 7.3.1 Directions in Opposition Proceedings

- 7.3.1.1 Direction to Stay an Opposition Pending Another Action

- 7.3.1.2 Further and Better Particulars

- 7.3.1.3 Time for Filing Evidence in a Substantive Opposition

- 7.3.1.4 Time for Filing Evidence in a Procedural Opposition

- 7.3.1.5 General Conduct of Proceedings

- 7.3.1.6 Further Directions

- 7.3.2 Directions that an Application Proceed in Different Name(s) - Section 113

- 7.4 Opposition Documents, Requirements and Amendments

- 7.4.1 Notice of Opposition

- 7.4.2 Statement of Grounds and Particulars

- 7.4.3 Amending Opposition Documents

- 7.4.4 Filing of Opposition Documents

- 7.5 Evidence

- 7.5.1 Presentation of Evidence

- 7.5.1.1 Written Evidence and Declarations

- 7.5.1.2 Oral Evidence

- 7.5.1.3 Physical Evidence - Special Considerations

- 7.5.2 Admissibility of Evidence

- 7.5.3 Evidence Filed Out of Time

- 7.6 Production of Documents, Summonsing Witnesses

- 7.6.1 Requests for Commissioner to Exercises Powers Under Section 210(1)(a) & 210(1)(c)

- 7.6.2 Basis for Issuing a Summons

- 7.6.3 Basis for Requiring Production of Documents or Articles

- 7.6.4 Reasonable Expenses

- 7.6.5 Complying with the Summons or Notice to Produce, Reasonable Excuses

- 7.6.6 Sanctions for Non-Compliance

- 7.6.7 Schedule to Requests for Summons or Notice to Produce

- 7.7 Withdrawal and Dismissal of Oppositions

- 7.7.1 Withdrawal of an Opposition

- 7.7.2 Dismissal of an Opposition

- 7.7.2.1 Requests for Dismissal

- 7.7.2.2 Dismissal on the Initiative of the Commissioner

- 7.7.2.3 Reasons for Dismissal

- 7.7.3 Withdrawal of an Opposed Application

- 7.8 Hearings and Decisions

- 7.8.1 Setting Down Hearings

- 7.8.1.1 Setting of Hearing

- 7.8.1.2 Location and Options for Appearing

- 7.8.1.3 Hours of a Hearing

- 7.8.1.4 Hearing Fee

- 7.8.1.5 Who May Appear at a Hearing?

- 7.8.1.6 Relevant Court Actions Pending

- 7.8.2 Hearings Procedure

- 7.8.2.1 Overview of Proceedings

- 7.8.2.2 Adjournment of Hearings

- 7.8.2.3 Contact with Parties Outside of Hearing

- 7.8.2.4 Hearings Involving Confidential Material

- 7.8.2.5 Consultation with Other Hearing Officers

- 7.8.2.6 Hearings and the Police

- 7.8.3 Ex Parte Hearings

- 7.8.4 Natural Justice and Bias

- 7.8.4.1 Rules

- 7.8.4.2 Waiving of Objection of Bias by Standing by until Decision Issued

- 7.8.4.3 Bias as a Result of Contact with Parties Outside of Hearing

- 7.8.4.4 Bias as a Result of Other Proceedings Involving the Same Parties

- 7.8.5 Principles of Conduct

- 7.8.5.1 Lawfulness

- 7.8.5.2 Fairness

- 7.8.5.3 Rationality

- 7.8.5.4 Openness

- 7.8.5.5 Diligence and Efficiency

- 7.8.5.6 Courtesy and Integrity

- 7.8.6 Decisions

- 7.8.6.1 Written Decisions

- 7.8.6.2 Time for Issuing a Decision

- 7.8.6.3 Publication of Decisions

- 7.8.6.4 Rectification of Errors or Omissions in Decisions

- 7.8.6.5 Revocation of Decisions

- 7.8.7 Further Hearings

- 7.8.8 Final Determinations

- 7.8.8.1 Overview of Proceedings

- 7.8.8.2 Applicant Does Not Propose Amendments

- 7.8.8.3 Opponent Withdraws the Opposition

- 7.8.9 Quality

- 7.8.10 Appointment of Hearing Officers and Assistant Hearing Officers, Hearing Officer Standards Panel, Hearing Officer Delegations

- 7.9 Costs

- 7.9.1 Principles in Awarding Costs

- 7.9.2 Scale of Costs, Variation of the Scale

- 7.9.3 Awarding Costs, Taxation

- 7.9.4 Security for Costs

- 7.9.5 Exemplary Situations in Awarding Costs

- 7.10 The Register of Patents

- 7.10.1 What is the Register

- 7.10.2 Recording Particulars in the Register

- 7.10.2.1 Recording New Particulars in the Register

- 7.10.2.2 Change of Ownership

- 7.10.2.2.1 Assignment

- 7.10.2.2.2 Change of Name

- 7.10.2.2.3 Bankruptcy

- 7.10.2.2.4 Winding Up of Companies

- 7.10.2.2.5 Death of Patentee

- 7.10.2.3 Security Interests

- 7.10.2.4 Licences

- 7.10.2.5 Court Orders

- 7.10.2.6 Equitable Interests

- 7.10.2.7 Effect of Registration or Non-Registration

- 7.10.2.8 Trusts

- 7.10.2.9 False Entries in the Register

- 7.10.3 Amendment of the Register

- 7.11 Extensions of Time and Restoration of Priority

- 7.11.1 Extensions of Time - Section 223

- 7.11.1.1 Relevant Act

- 7.11.1.2 Subsection 223(1) - Office Error

- 7.11.1.2.1 Extensions under Subsection 223(1) to Gain Acceptance

- Annex A - Section 223(1) Extension of Time for Acceptance File Note

- 7.11.1.3 Subsection 223(2) - Error or Omission and Circumstances Beyond Control

- 7.11.1.3.1 The Law

- 7.11.1.3.2 Subsection 223(2)(a) - Error or Omission

- 7.11.1.3.3 Section 223(2)(b) - Circumstances Beyond Control

- 7.11.1.3.4 Filing a Request under Subsection 223(2)

- 7.11.1.3.5 The Commissioner's Discretion

- 7.11.1.4 Subsection 223(2A) - Despite Due Care

- 7.11.1.5 Common Deficiencies in Requests under Section 223(2) or (2A)

- 7.11.1.6 Advertising an Extension - Subsection 223(4)

- 7.11.1.7 Extension of Time for an Extension of Term

- 7.11.1.8 Grace Period Extensions

- 7.11.1.9 Extension of Time to Gain Acceptance

- 7.11.1.10 Examination Report Delayed or Not Received

- 7.11.1.11 Co-pending Section 104 Application - Budapest Treaty Details

- 7.11.1.12 Payment of Continuation or Renewal Fees Pending a Section 223 Applicaiton

- 7.11.1.13 Person Concerned: Change of Ownership

- 7.11.1.14 Date of a Patent Where an Extension of Time is Granted to Claim Priority

- 7.11.2 Extensions of Time - Reg 5.9

- 7.11.2.1 Requesting an Extension of Time

- 7.11.2.2 Application of the Law

- 7.11.2.3 Justification for the Extension

- 7.11.2.4 Discretionary Matters

- 7.11.2.5 Period of an Extension

- 7.11.2.6 A Hearing in Relation to an Extension

- 7.11.2.7 Parties Involved in Negotiations

- 7.11.2.8 Review of a Decision to Grant or Refuse an Extension

- 7.11.2.9 "Out of Time" Evidence

- 7.11.3 Restoration of the Right of Priority Under the PCT

- 7.12 Extensions of Term of Standard Patents Relating to Pharmaceutical Substances

- 7.12.1 Section 70 Considerations

- 7.12.1.1 Pharmaceutical Substance per se

- 7.12.1.2 Meaning of Pharmaceutical Substance

- 7.12.1.3 Meaning of "when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology"

- 7.12.1.4 Meaning of "mixture or compound of substances"

- 7.12.1.5 Meaning of "in substance disclosed"

- 7.12.1.6 Meaning of "in substance fall within the scope of the claim"

- 7.12.1.7 Included in the Goods

- 7.12.1.8 First Regulatory Approval Date

- 7.12.2 Applying for an Extension of Term

- 7.12.2.1 Documentation Required

- 7.12.2.2 Time for Applying

- 7.12.2.3 Extension of Time to Apply for an Extension of Term

- 7.12.3 Processing an Application for an Extension of Term

- 7.12.3.1 Initial Processing

- 7.12.3.2 Consideration of the Application

- 7.12.3.3 Grant of Application for Extension of Term

- 7.12.3.4 Refusal of Application for Extension of Term

- 7.12.4 Calculating the Length of the Extension of Term

- 7.12.5 Patents of Addition

- 7.12.6 Divisional Applications

- 7.12.7 Oppositions to an Extension of Term

- 7.12.8 Relevant Court Proceedings Pending

- 7.12.9 Rectification of the Register

- 7.13 Orders for Inspection of non OPI Documents

- 7.13.1 Documents not-OPI by direction of the Commissioner - Regulation 4.3(2)(b)

- 7.13.2 Inspection of non-OPI Documents

- 7.14 Appeals ART, ADJR, The Courts

- 7.14.1 Appeals to the Federal Court

- 7.14.2 Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) Review

- 7.14.3 Judicial Review (ADJR)

- 7.14.4 Other Court Actions Involving the Commissioner

- 7.14.5 Section 105 Amendments

- 7.15 Computerised Decisions

- 8. Superseded Legislation and Practice

- 8.1 Summary of Relevant Legislative Changes

- 8.2 General Approach to Examination

- 8.2.1 Restriction of the Report

- 8.2.2 Not All Claims Previously Searched and/or Examined

- 8.2.3 Law and Practice Differences

- 8.3 Amendments

- 8.3.1 Allowability of Amendments to Complete Specifications

- 8.3.2 Allowability Under Section 102(1)

- 8.3.3 Allowability Under Section 102(2) - General Comments

- 8.3.4 Amendments to a Provisional Specification

- 8.3.5 Opposition to Amendments - Standard Patents

- 8.4 Novelty

- 8.4.1 Introduction

- 8.4.2 Prior Art Information

- 8.4.3 Exclusions

- 8.4.4 Doctrine of Mechanical Equivalents

- 8.4.5 Basis of the "Whole of Contents" Objection

- 8.5 Inventive Step

- 8.5.1 The Statutory Basis for Inventive Step

- 8.5.2 Prior Art Base

- 8.5.3 Assessing Inventive Step in Examination

- 8.5.4 Common General Knowledge

- 8.5.5 Determining the Problem

- 8.5.6 Identifying the Person Skilled in the Art

- 8.5.7 Could the PSA have Ascertained, Understood, Regard as Relevant and Combined the Prior Art Information

- 8.5.7.1 Ascertained

- 8.5.7.2 Understood

- 8.5.7.3 Regarded as Relevant

- 8.5.7.3.1 Document Discloses the Same, or a Similar, Problem

- 8.5.7.3.2 Document Discloses a Different Problem

- 8.5.7.3.3 Age of the Document

- 8.5.7.3.4 Would the Person Skilled in the Art Have Used the Document to Solve the Problem

- 8.5.7.4 Does the Document Constitute a Single Source of Information

- 8.5.7.5 Could the PSA be Reasonably Expected to Have Combined the Documents to Solve the Problem

- 8.6 Innovative Step

- 8.7 Section 40 Specifications

- 8.7.1 Overview

- 8.7.2 What is the Invention?

- 8.7.2.1 General Considerations

- 8.7.2.2 Approach in Lockwood v Doric

- 8.7.2.3 Consistory Clause

- 8.7.2.4 Requirement for Critical Analysis

- 8.7.2.5 "Essential Features" of the Invention

- 8.7.3 Full Description - Best Method

- 8.7.3.1 Date for Determining Full Description

- 8.7.3.2 Can the Nature of the Invention be Ascertained?

- 8.7.3.3 Compliance with Subsection 40(2) is a Question of Fact

- 8.7.3.4 Enabling Disclosures

- 8.7.3.5 Effort Required to Perform the Invention

- 8.7.3.6 Different Aspects Claimed in Different Claims

- 8.7.3.7 Inclusion of References

- 8.7.3.8 Trade Marks in Specifications

- 8.7.3.9 Colour Drawings and Photographs

- 8.7.4 Claims Define the Invention

- 8.7.5 Claims are Fairly Based

- 8.7.5.1 General Principles

- 8.7.5.2 Sub-Tests for Fair Basis

- 8.7.5.3 Relation Between the Invention Described and the Invention Claimed

- 8.7.5.4 Only Disclosure is in a Claim

- 8.7.5.5 Alternatives in a Claim

- 8.7.5.6 Claiming by Results

- 8.7.5.7 Reach-Through Claims

- 8.7.5.8 Claims to Alloys

- 8.7.6 Provisional Specifications

- 8.7.7 Complete Applications Associated with Provisional Applications

- 8.8 Patentability Issues

- 8.9 Abstracts

- 8.10 Divisional Applications

- 8.10.1 Application

- 8.10.2 Priority Entitlement

- 8.10.3 Time Limits for Filing Applications

- 8.10.4 Subject Matter

- 8.10.5 Amendment of Patent Request - Conversion of Application to a Divisional

- 8.10.6 Case Management of Divisional Applications

- 8.11 Priority Dates and Filing Dates

- 8.11.1 Priority Date of Claims

- 8.11.2 Priority Date Specific to Associated Applications (Priority Dociment is a Provisional)

- 8.11.3 Priority Date Issues Specific to Convention Applications

- 8.11.4 Priority Date Issues Relating to Amended Claims

- 8.12 Examination

- 8.13 Modified Examination

- 8.14 Petty Patents

- 8.15 National Phase Applications

- 8.15.1 Key Features of the Legislation

- 8.15.2 National Phase Preliminaries

- 8.15.3 Formality Requirements

- 8.15.4 Priority Sources

- 8.15.5 Determining Whether Amendments Made Under Articles and Rules of the PCT are Considered During Examination

- 8.15.6 Amendments During Examination

- 8.16 Convention Applications

- 8.16.1 Convention Country Listing

- 8.16.2 Convention Country Status Change

- 8.16.3 Basic Application Outside 12 Month Convention Period

- 8.16.4 Convention Priority Dates

- 8.17 Patent Deed

5.2.2 Working with Case Law

When reading a decision of a court, consider:

What court decided the case;

Is that decision binding; and

What principle does the case stand for?

The doctrine of precedent

Precedent means that judges must follow interpretations of the law made by judges in higher courts, in cases with similar facts or involving similar legal principles.

In 1966, the UK House of Lords justified this principle as follows:

"Their Lordships regard the use of precedent as an indispensable foundation upon which to decide what is the law and its application to individual cases. It provides at least some degree of certainty upon which individuals can rely in the conduct of their affairs as well as a basis for orderly development of legal rules." ([1966] 3 All ER 77, [1966] 1 WLR 1234).

The doctrine of precedent is sometimes known by its Latin equivalent ‘stare decisis et non quieta movere’, stare decisis for short, which means:

'to adhere to precedent and not to unsettle things which are established.'

For example, a decision of a judge in the High Court is binding on judges in all lower courts. However, a decision is only binding on other courts in the same jurisdiction. A decision of a state Supreme Court is not binding on the Supreme Court of a different state.

Some of the rules that make up the doctrine of precedent are:

A judge follows the law declared by judges in higher courts in the same jurisdiction in cases with similar facts;

A court must give reasons for its decision in a case. The reasons should include an explanation of why the court has chosen to follow, or not follow, a previous decision that is similar to the case before it. When an earlier decision is not followed it is said to be distinguished from the earlier case;

Most courts are not bound to follow their own earlier decisions, although they often do. For example, the High Court of Australia follows its own earlier decisions in most cases but is not required to do so;

The decisions of courts outside Australia are not binding on Australian courts, although they can be used to assist or guide Australian courts in making decisions on new facts. For example, if a matter before an Australian court is unusual or difficult, judges and lawyers might look to overseas decisions for guidance or comparison; and

The decision of the highest court within a particular jurisdiction is final. The highest court is the court to which the final appeal can be made. In the Australian system, this is the High Court.

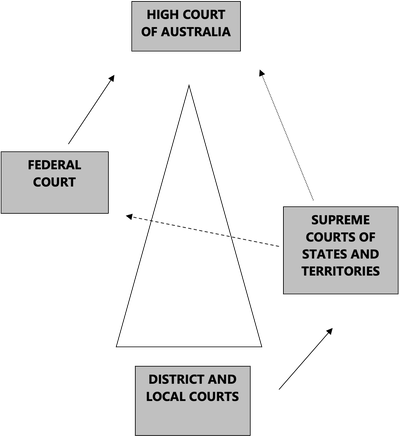

Clearly an understanding of which decisions are binding on a judge depends on the hierarchy of courts in the jurisdiction.

Court hierarchies

The law courts in Australia form a hierarchy. The hierarchy of courts is an essential part of our justice system. It allows:

lower courts to follow precedents made by higher courts, this ensures consistency while still allowing the law to be modified over time;

for appeals to higher courts; and

particular courts to specialise in hearing particular types of cases and interpreting particular statutes.

In summary, the hierarchy of courts that is relevant for us is:

High Court of Australia

The High Court is the highest court in Australia. It was created by Section 71 of the Constitution. It has appellate jurisdiction over all other courts, that is, it is the highest possible court of appeal. The functions of the High Court are to interpret and apply the law of Australia; to decide cases of special federal significance including challenges to the constitutional validity of laws and to hear appeals, by special leave, from Federal, State, and Territory courts.

In most cases, the appellate divisions of the Supreme Courts of each state and territory and the Federal Court are the ultimate appellate courts. The Full Court of the High Court is the ultimate appeal court for Australia.

Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court was created by the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976. It primarily hears matters relating to corporations, trade practices, industrial relations, bankruptcy, customs, immigration, and other areas of federal law. It has original jurisdiction in these areas. It also has the power to hear appeals from a number of tribunals and other bodies and, in cases not involving family law, from the Federal Magistrates' Court of Australia.

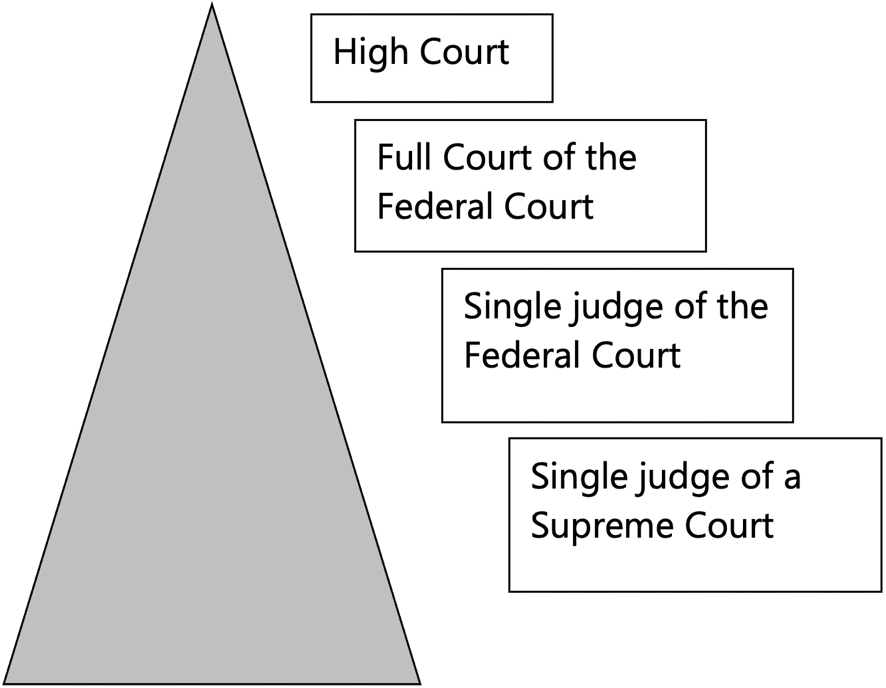

The Federal Court is below the High Court in the hierarchy of federal courts, and decisions of the High Court are binding on the Federal Court. There is an appeal level of the Federal Court (the Full Court of the Federal Court), which consists of several judges (usually three but occasionally five in very significant cases).

State and territory courts

Each state and territory has a court hierarchy of its own, with the jurisdictions of each court varying from state to state and territory to territory. However, all states and territories have a Supreme Court which is a superior court of record and is the highest court in that state or territory. These courts also have appeal divisions, known as the Full Court or Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court (in civil matters), or the Court of Criminal Appeal (in criminal matters).

Decisions of the High Court are binding on all Australian courts, including state and territory Supreme Courts.

Most of the states have two further levels of courts, which are comparable across the country. The District Court (or County Court in Victoria) handles most criminal trials for less serious indictable offences and most civil matters below a threshold (usually around $1 million). The Magistrates' Court (or Local Court) handles summary matters and smaller civil matters.

Hierarchy of courts in patent matters

The major types of court actions in relation to patents are infringement and revocation proceedings.

These actions are initiated in the Federal Court or a Supreme Court (s120, s134, and s155). Original actions may only be heard by a single judge of these courts (s156). The only direct court of appeal is the Federal Court (s158). Appeal from the Federal Court is to a Full Court of the Federal Court, and then to the High Court (s158).

Therefore, the hierarchy in patent matters is:

Amended Reasons

| Amended Reason | Date Amended |

|---|---|

Accessibility fix – alternative text for images |

|

Published for testing |